Guillermo del Toro is speaking : “I want to teach again in the animation school. I want to teach because with cinema, form is content. It is the same thing. You cannot separate them. I always say if we do not treat cinema like a visual art, if we only concentrate on the story and the characters, we are diminishing it. A lot of the time when we talk about cinema, we say ‘What is the movie about?’ ‘Well, it’s about a guy who steals a motorcycle.’ You describe the story and the characters but you never disclose the vibrancy of the montage, the color palate, the composition, the movement, the symphonic nature of the craft. For example, it’s like we were discussing a painting by Van Gogh : ‘What is the painting about?’ ‘It’s a fucking room with a bed, a window, and a chair’. I am not going to see the painting. What the painting is about is the way the brush stroke happens, and the way the color composition is balanced and the way the colors exist and form an illusion of volume. You describe it formally. And we do not give that level of discussion to cinema.”

There we have it. I haven’t edited this passage. I am offering it to you as it is. It sums up the extraordinary talent, the unique quality of the artist Guillermo del Toro. And then, you’ll agree, this quotation shows us why Guillermo the artist is an ideal interviewee for Exhibition.

One morning in July, Edwin, Boris and I, a little bit like in the Marie Laforêt song (one for the oldies) meet for breakfast in a lovely hotel in the 6th.

Guillermo has come from the Rue Dauphine where he has bought a small apartment. The day before he was in Nor- mandy, where he’s found an old country pile to do up. Another pied-à-terre to add to those he already has in Toronto, Los Angeles and (most recently) in Portugal, where he intends to spend more and more time.

This gentle man-mountain, this bon viveur who is funny, serious, and meticulous, continues to plough his own creative fur- row, whilst helping other talents to blossom.

“After I won my Oscar at the beginning of the year for The Shape of Water, I think what changed for me is that I realized for a very brief time I have the chance to create something for the people coming after me. I want to create 2 or 3 animation centres : one in the States, one in Europe,and the first, opening next March, in Guadalajara, the town I grew up in in Mexico. I already have encountered quite a few talented young animators. We’re in the process of constructing the warehouses that are going to be used to build and to film stop-motion puppets, as well as class- rooms and teaching studios. I’m going to fund scholarships for students to go to London, Paris, Eastern Europe and Japan, anywhere where there’s talent and the animation scene is vibrant.”

Animation has always been there. It will be central to a new phase in his career. "I want to direct three more live action movies for sure - and then direct animation. I’ve been preparing for this for many years by directing a TV series I have called Trollhunters.” According to Guillermo, "one of themost beautiful animated films of the past few years is La Tortue Rouge : it’s an amazing meditation on humanity and a cosmic fable about the place of man in nature. I think that the highest form of filmmaking you can obtain is animation because you control everything and at the same time you are creating. There’s a unique potential in animation. If I animate a character moving, it is all of us, it is humanity moving. It‘s not a specific actor, no matter how good he is. We watch movement or the way light hits it in a much more painterly way in animation than we watch it in a live action movie, so I am very intrigued by being able, for at least some time, to direct animation here and there.”

Guillermo is generous in everything he is and everything he does. An immensely talented artist, an extremely compelling teacher, he opens doors for people – windows even! His education prepared him for that. “ My father was a high middle class businessman; he had a car dealership. One day he won the lottery and became very rich. He bought a big house for us all, with a big library, it was the classics so I was reading Victor Hugo, Mark Twain, Jack London, Robert Louis Stevenson, but the French writer who made a massive impression on me was Guy de Maupassant, then Marcel Schwob, who isn’t well known here, also made a very big impression on me. He was admired by Oscar Wilde, who praised his musica- lity. That’s what made me learn French. To be able to hear the musicality.”

Guillermo, with his nine films and twenty-three scripts, works that are both deep and delicate, has managed to marry monsters, fairies and major events in history in a unique way. We want to live with these monsters, to sit down to dinner with the aquatic Elisa, whose senses are so much richer than ours. In Pan’s Labyrinth, through the story of Vidal and Ophelia, he revisits the Spanish Civil War and juxtaposes the cruelty of the world with magic. His use of fantasy, has, from the beginning, enabled him to transcend genre cinema. He makes a living language of it, which feeds on anything and everything. He is in a state of permanent renewal. “Monsters don’t have any social constraints, they have permission to be fallible. I always say perfection is impossible, but imper- fection is something we can all aspire to.”

Between his fried eggs, his croissants, his juice, his coffee, we’ve talked about everything, about all his worlds, whilst trying to talk about him. It’s fortunate that he’ll be back in Paris. We’ll have to go with him to the market with his “lit- tle cart with wheels.” There are so many things to discover.

“The funny thing about what I do is that I have been doing it since I was a kid until now in the same way. I have evolved but I have not changed. If I had a conversation with me at age 10 I would like myself; I would say, ‘I like this old guy’. At school in Mexico I made a film about a monster on Super-8. It was bad. It was about a monster who came out of the toilet, created panic and then went back to the toilet. Everyone was happy because they could see the school on screen, but I threw it out. And today, I win the Oscar, I go on stage, I turn towards the room, towards Hollywood, and I am still then years old. Like at Cannes, when you and Thierry Frémaux asked me to write a parable about monsters, for the 70th anniversary gala. I didn’t write it, predictably. I was really nervous. And I turned round and I saw Lynch, Haneke, George Miller, the masters of the art. You remember, I froze. Everyone saw that I was paralyzed and so they got to their feet, applauding. And then, I started over.” This was more than just the standard blush of shame ! This man is astounding. If monsters are capable of such humanity, I want to live among them.

I ask him if one day he’ll manage to make At the Mountains of Madness, adapted from the H.P. Lovecraft story, on which he’s been working since 1993. The look he gives me suggests that he’s given the project up. The living perfection of animation has (almost) entirely won him over. “In fantasy, like in animation, stories don’t change you, they reveal who you are. Like the princess in Pan’s Labyrinth, she doesn’t become a princess, she is revealed to be a princess. The fantasy doesn’t change her; it makes her aware. For me, fantasies are a way to look at the world in a more intelligent way, more fully than facts. The two oldest forms of storytelling are parable and fairy tale. The novel, like realism, came later.”

Through his way of living, finding inspiration, reflecting and thinking about the worlds he imagines, this Mexican is at home everywhere. And sometimes at home among us. To meet him, in the 6th or in his films, is to never want to leave him.

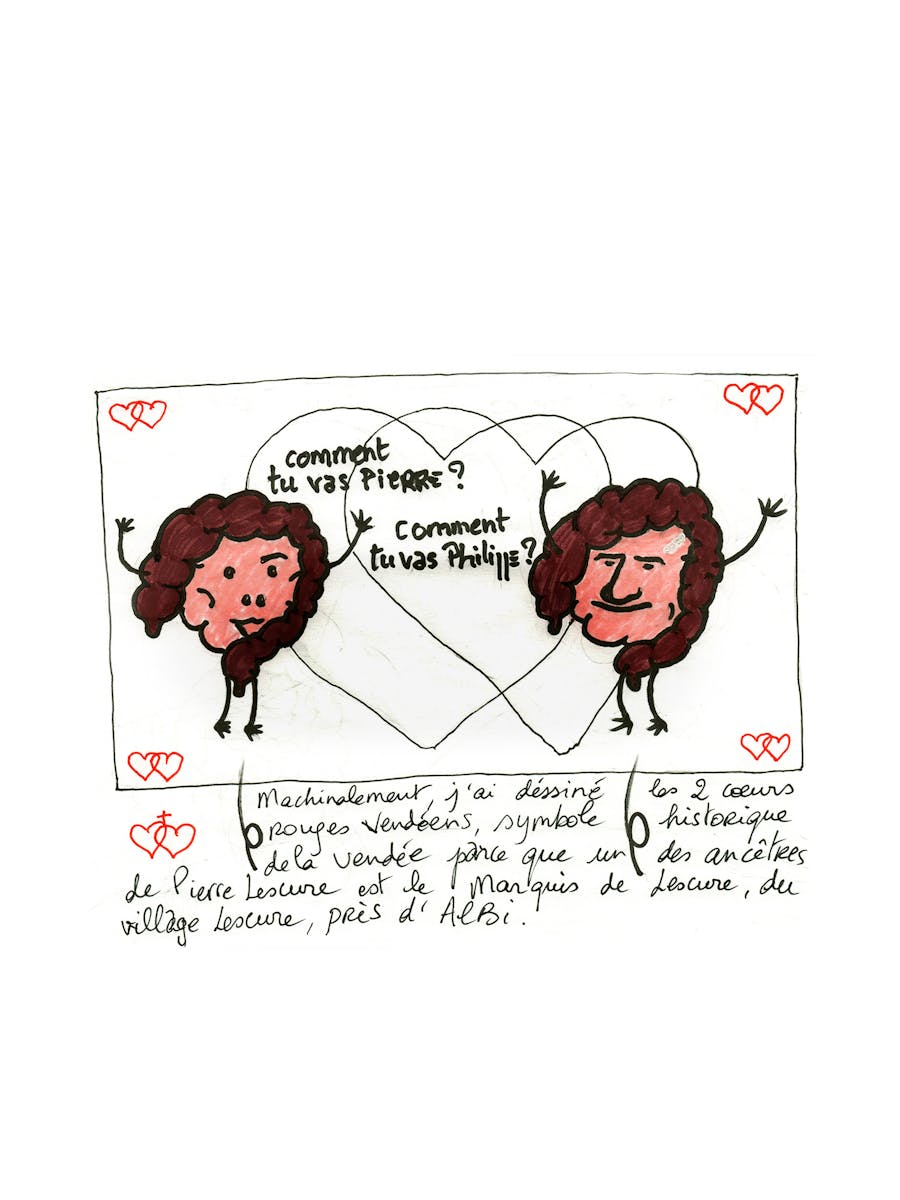

Sara & Emma Bielecki

Sara & Emma Bielecki