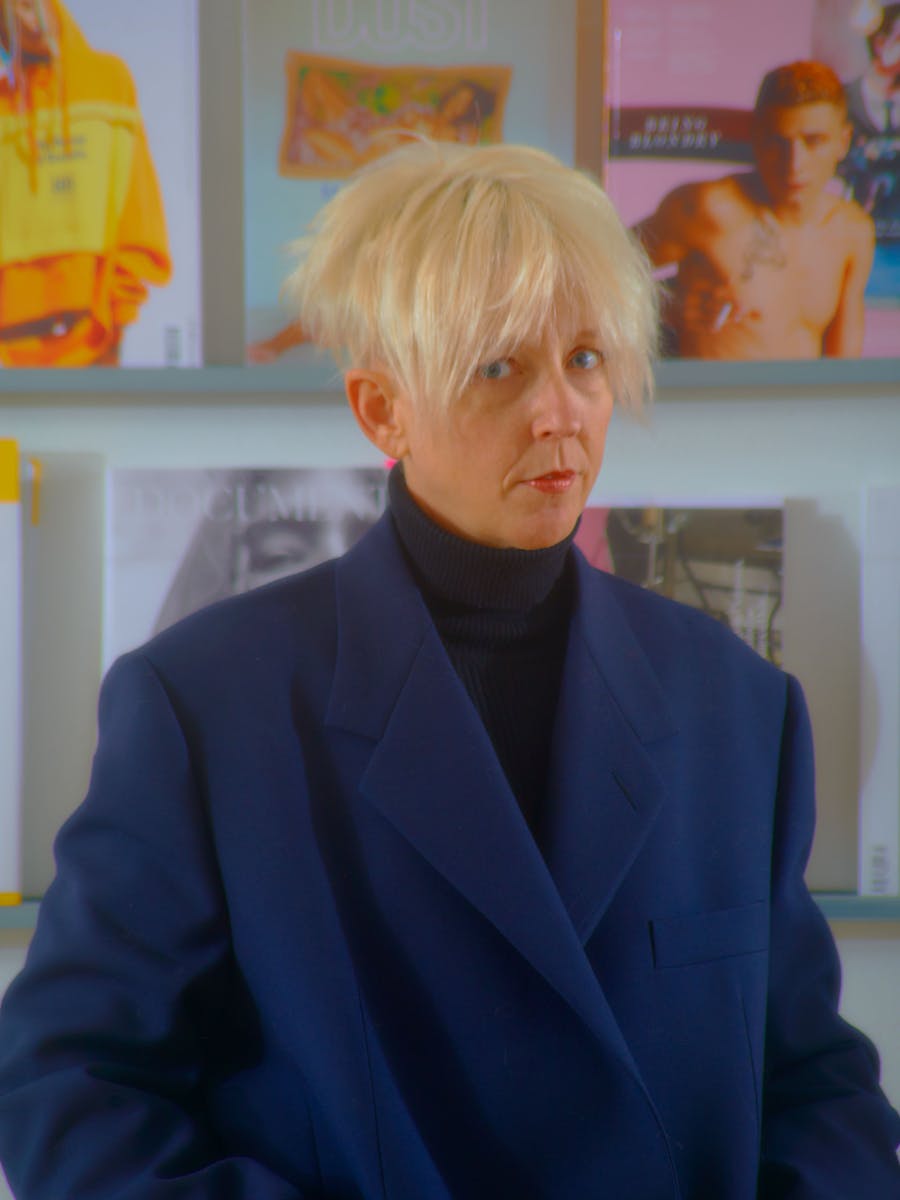

From The Excess Issue

If you don’t believe in fate, this interview could convince you otherwise. From Texas, his birthplace, to the gold of Place Vendôme, take a mystical trip with Daniel Roseberry, enlightened soul and artistic director of Schiaparelli.

Plano, Texas, 1987. A little boy, the son of a pastor and an artist mother, stares at aTV screen, spellbound by MTV. A youngpop star, styled like a bad boy, dressed all in black, performs his new single, about to hit n°1 on the Billboard Hot 100. The video, directed by Martin Scorsese, is none other than Michael Jackson’s “Bad”. It is a revelation, like a window into another world. An imaginary world, populated by pop inspirations, cult figures and chimerical creatures. A world that Daniel Roseberry has never stopped exploring in his designs, from the pews of his father’s church to the salons of the Maison Schiaparelli in Paris, with their unbeatable view on the imperious Place Vendôme.

Paris, June 2024. In the cushioned, intimate drawing-room of the Hôtel Salomon de Rothschild, Daniel Roseberry presents his show for Haute Couture Fashion Week, FW24. In the shadows, you can just make out Kelly Rutherford, Kylie Jenner and Doja Cat in the front row, but this season, the designs are in the spotlight. After a series of shows that attracted attention for the star-power of the celebrities attending them, Daniel Roseberry is now asserting his identity as a designer and revealing the extent of his vision. With “The Phoenix”, he is pursuing the Schiaperellian idea of metamorphosis. The ready-to-wear SS25 show will be a defining moment: the Schiaparelli woman is getting ready once and for all to leave the fancy neighbourhoods and enter reality. We discuss pop influences, the creative process, and vital excess with Daniel Roseberry.

Elsa Schiaparelli’s Salon place Vendôme where we are today is perfect for our theme, The Excess Issue. What does this grandiloquent place evoke for you?

D.R. We’re in Elsa Schiaparelli’s original Salons from the early 30s, designed by

Jean-Michel Frank. Obviously, the grandeur of the space, the gold of the salons and the idea that we’re the only Couture House on Place Vendôme, you can feel the sense of history. It’s certainly a very powerful space to create. It sort of brainwashes you

in the best way possible.

Do you remember your first memory of this place?

D.R. That was just before I interviewed for the Schiaparelli job. It was wintertime. I was sitting on a park bench in the Tuileries, I had my project with me and I remember being in the park with all these dead trees and this feeling, both so excited and very alone. It was one of those moments where you sort of feel the weight of history on your shoulders, even if it’s just your own personal history. And I knew I had the job. I just knew it. I was absolutely convinced that I was the best person for the job.

Before that, you had already been to Paris several times with Thom Browne during fashion week?

D.R. Indeed. I remember we showed a Men’s collection at the Communist Party Headquarters in Paris, and Thom had asked me to be in the show to help dress the models in front of the audience. It was traumatizing. With Thom, shows have always been a baptism of fire. And they shaved my beard for the first time since high school. So I was unrecognizable, for the best, I think.

You worked with Thom Browne for 10 years in New York. What did you learn from this first experience in the fashion world?

D.R. When I got the invitation to join Thom Browne’s team, I went online to look at the collections but I knew, I felt this whisper that I was supposed to go there. The connection with Thom was immediate. I learned mostly two things. One was just construction. Many of the factories that we work with today are the same factories that I was introduced to through Thom: the cashmere from Scotland, the wool from Ireland, the shoes from Italy… But mostly, I learned what would be expected of me as a creative director by watching Thom handle the burdens and the beautiful parts, the glory of being a creative director. This helped me a lot later, when I moved to Paris.

It must have been a big change for you. As an American running a Parisian fashion house, how do you combine the two cultures into a single vision?

D.R. By staying true to myself. My friend Hanya Yanagihara told me when I started : “You have to tell a story that only you can tell”. The story of a preacher’s son from Plano, Texas, who sort of became a real person in New York and has found his way to Paris. I’m not trying to be someone else. There’s a beautiful sort of outsider’s perspective that feels true to Schiaparelli as she was an Italian working in Paris. It’s like being an observer. I don’t feel Parisian at all, but I have immense respect for them and I think there has always been this tension, but also this beautiful complementarity between us; this combination of cultural creation, knowhow and traditions that is truly unique.

Craftsmanship is a very important part of your work. Can you tell us about your creative process?

D.R. It starts with words. The words are a way of setting an intention, like my compass, my guide for the season. Lately, you could call them a mantra. It’s like a way of giving structure. Otherwise, it’s too overwhelming. I’m a triple Virgo, so I’m very practical and perfectionist. So, we start by looking at the season that just happened, I look at what people respond to, what felt triumphant, and then what felt like a failure, like a missed opportunity. That’s where I start with the team.

Is it the same creative process for couture and ready-to-wear?

D.R. I always say to the team that couture is about exploring, ready-to wear is about exploiting, but not in the negative way. It’s more about capturing the concepts, the ideas that are born in the couture, and translating that into something for everyday life. My rule is, when you’re wearing a Schiaparelli piece, you should be stopped in the street immediately and someone must say: “Oh my God, what is that piece?”. It’s a conversation starter. That’s why I say the everyday excess is something that is so vital.

For the Spring/Summer 2025 season, you’ve decided to focus on ready-to-wear.

D.R. There’s so much space in my mind to find exactly that special niche for Schiaparelli ready-to-wear in the general context. For me, it’s almost like a chess game, we have to find the perfect little spot. At first, we wanted to have the most visible collection of the fashion week. But now, it’s a completely different goal. Instead of visibility, we want legitimacy, we want the person who loves Schiaparelli to start to think about it every day. So it’s a very rational work at the beginning. That’s one thing I learned from Thom Browne as well, when you’re inside a rigor and a structure, you can be even more creative. When you have goals, fantasy always happens.

Does the Spring/Summer 2025 ready-to-wear show mark a turning point for you?

D.R. It’s been a super intense creative output period for me. I think this collection will go to another level. I really have wanted to make sure that it feels so independent from the couture. Indeed, when has a designer, or a house, both defined what couture should look like at a given moment and also said something powerful about the way you should dress in the morning? It’s a short list. For example, McQueen changed the way a couture show was, but didn’t change the way women dress. Miuccia Prada has changed the way women dress, but has never defined Haute Couture. I think you have to go back to the masters to find that. I think Dior did it, Elsa Schiaparelli did it, that’s how ambitious we are.

A few words about Elsa Schiaparelli. How do you imagine her?

D.R. I have embraced the enigma of who she was. I have nothing but respect for the radical approach that she had to business as an entrepreneur. As a woman, she was a futurist thinker. I do not think she would have wanted a creative director here, running her house, wringing his hands. She was ferocious as a woman and as a designer, but I leave it as a legacy in a way.

Who is the Schiaparelli woman?

D.R. For me, she’s gone global. She is everywhere. The world is her living room. I think that she’s looking for something that feels extraordinary, like an antidote to our times. Linda Fargo, from Bergdorf Goodman, said to me: “Your clients don’t buy the ready-to-wear, they collect the ready-to-wear”. That’s a huge difference.

Do you think the value of clothes lies in time?

D.R. Absolutely. Future vintage.

And what about arts? Because Elsa Schiaparelli was surrounded by the surrealist movement and great figures of the art world such as Cocteau, Cecil Beaton and Man Ray.

D.R. When I started at Schiaparelli, the conversation was: when are we going to start doing collaborations with artists? And I thought, I don’t want the legitimacy of the house to be linked to any other artist. What seems most modern to me today is this idea that I’m collaborating with Elsa Schiaparelli herself. I was also very influenced by Lalanne or Egyptian art and the idea of molding body parts. For me, the human body presents itself as a kind of universal and timeless point of contact for the fine arts, like a modern surrealist touch. It seems to me much newer and more exciting than a luxury house collaborating with an artist to create buzz. When people see ready-to-wear, they think it’s couture. I love that because they say: “Oh my God, this is art or this is fashion as art?”.

Through their art, the Surrealists sought to provoke strong emotional reactions. For Dali, for example, painting had an almost sexual dimension. What reactions do you want to elicit?

D.R. I want to have a creative impact. But our culture is changing so fast, almost every month, the goals are changing. I don’t feel like Dali at all, or like McQueen for instance. McQueen said: “I don’t go to therapy. The shows are my therapy”. He was forcing people to experience this with him. I kind of feel like it’s the opposite for me. I’m constantly absorbing what people need to see in order to feel inspired. And I’m adapting to that. I hate to say it like this, but it’s more an act of service to both the client and to the culture.

Today, it seems that the show is not only on the catwalk, but also in the front row. Do you think the front row has become an integral part of the show?

D.R. If you had asked me that question a year and a half ago, I would have said: “absolutely, it’s critical”. With Kylie Jenner and Doja Cat, I wanted them to take part in the last shows because they’ve been so supportive, but I didn’t want to do something where people would talk more about the guests than the clothes. I think there’s a sense of exhaustion and fatigue that people have about seeing celebrities break the internet. What feels more fresh is for the conversation to be about the clothes, the craft and the creations themselves. Celebrity games are about the moment, which means it’s already over.

Let’s talk about pop culture. It’s an essential source of inspiration in your work.

D.R. I’m a student of the 90s in the US, a golden age of pop culture. So, that whole era of Catwoman, Michael Jackson, Madonna, MTV, Whitney Houston… It’s where I learned as a kid to dream about a world outside of my present experience. I remember watching the “Bad” music video on MTV for the first time. I didn’t know what I was looking at, but I was fascinated by everything. Pop culture is an imaginary world whose components are deeply rooted in us, and always resurface. Again, once the structure is in place, all these elements become a playground.

There’s a real contrast between the pop culture you enjoyed as a child and the religious environment in which you grew up in Plano, Texas.

D.R. I’m very grateful to be from Texas and to have had this experience in my youth, even though it was a really religious and conservative environment. I always felt safe with my family, I felt a lot of love from them. A lot of that period feels sort of like a blur. I don’t think about it very often. I was put into a really conservative Christian school system, so I was in a uniform from the time I was 11 through the time I was 33, because I also had a uniform at Thom Browne. So, I wore a uniform basically my whole life.

Your dear mother, Fran Roseberry, an artist and calligrapher, had a great influence on you and taught you to draw.

D.R. Probably the greatest gift anybody ever gave me was the ability to communicate through my drawing. But my mother was also teaching me how to deal with frustration, because I wanted it to be perfect immediately. She taught me about patience and the fact that the creative process is not instant.

Are you a man of faith?

D.R. Oh, God. I do believe that I am a man of faith. I feel like my whole life is a constant dialogue with God, with the divine, with my creator. One of my best friends is a raging atheist, and I think she is also in constant dialogue with her creator. It’s a different dialogue, but it’s all the same. It’s all about that. For me, it’s also a way of feeling less alone. Faith is like a mechanism by which we can feel like there’s someone working with us, in creating our lives. Being a fashion designer, we’re alone sometimes. These big walls, it can be overwhelming. There is this expression “there’s less oxygen at the top”. So, I do think that my faith, which feels really personal and really uniquely mine, is essential to me.

What do you think of the world we live in? Do we live in a world of excess?

D.R. I think the temperature of the room feels like it’s getting hotter and hotter, like the planet. It just feels like the train is getting faster and faster. For me, generosity is the key word, the ultimate luxury.

What is your favorite word in French?

D.R. “Poubelle”.

I didn’t see it coming. One last question, if you could have dinner with any three people in the world, who would you choose?

D.R. I would say Audrey Hepburn, Hanya (Yanagihara), and I think, weirdly enough, I’d want to know from Abraham Lincoln. Someone who changed the course of history. I would want to learn more about how to be a better man from someone like him.