From the Faces issue

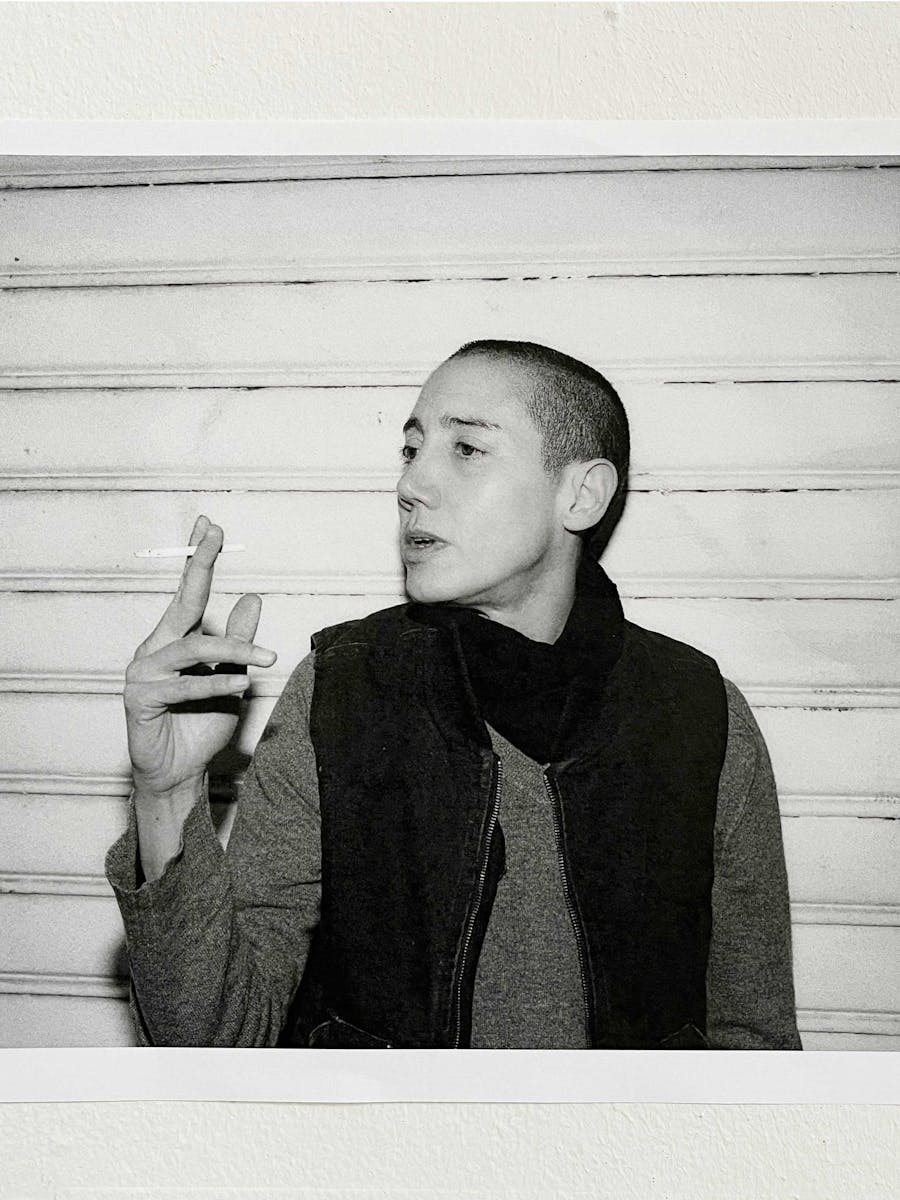

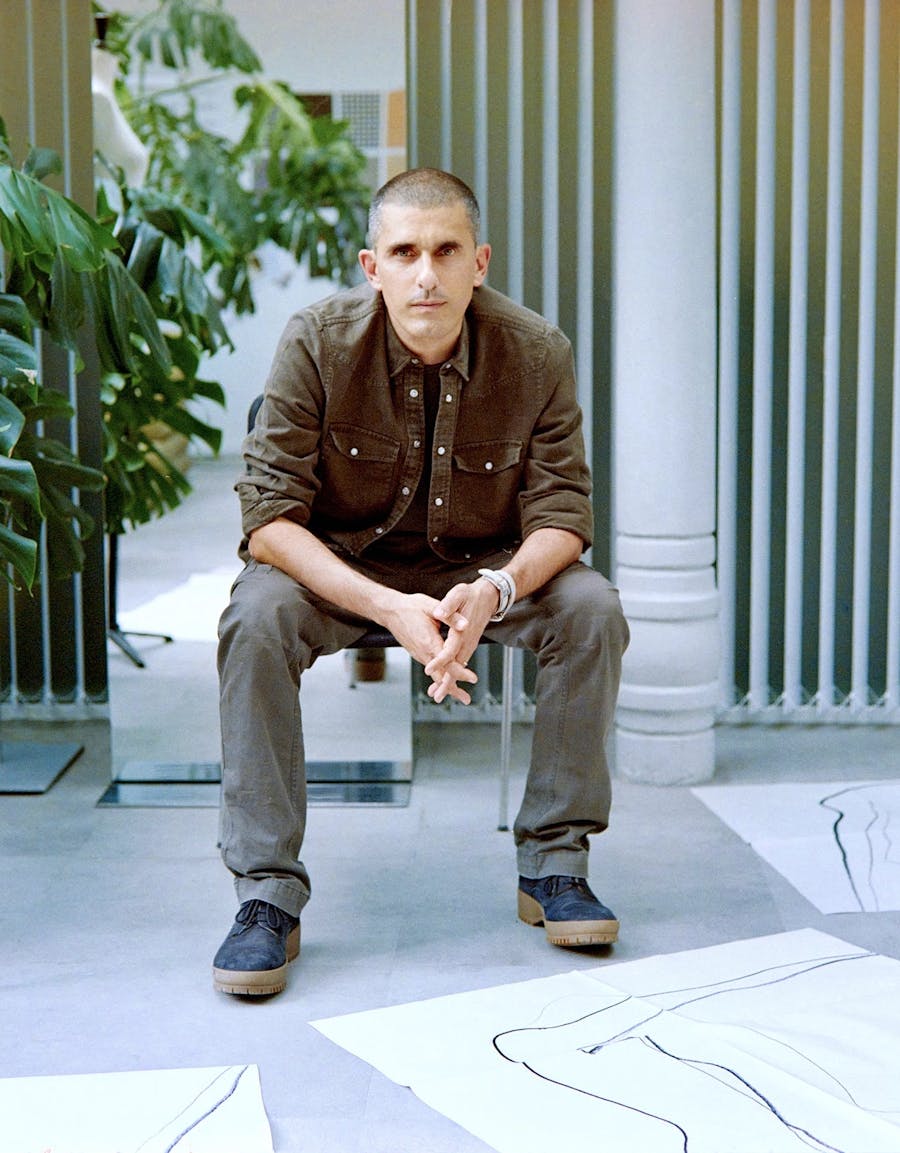

In an era in which selfies and Instagram Face have become ubiquitous, we discussed the invention of the face and its social significance across history with David Le Breton, author Faces, a work of philosophy.

“The greater the importance a society accords to individuality, the greater the value of the face”. It is with these words that David Le Breton, professor of sociology and anthropology, describes the importance of the face in our hyperindividualized, digital societies. As ambivalent as it is fascinating, it is in this part of the body, “the most human part of man”, that a person finds their sovereignty and proper identity. The face takes us to the border between the visible and the invisible, the collective and the intimate.

Why do faces fascinate us so much?

Because they are the sign of the extreme singularity of each of us. The difference between people is first experienced by the difference between faces. It is through them that we are recognized, identified with a certain age, a sex, a skin colour. It is the first sign of identity which allows us to exist with others and to enjoy recognition in the eyes of others.

Do we ascribe more importance to the face today?

Yes, for an incredibly long time, humans did not pay attention to faces. For them to detach themselves from the body and take on an increased value, we had to wait for a certain kind of individualization of the social link. The point of rupture appeared with the Renaissance, when some people – basically nobles, politicians, condottiere – detached themselves from the community to become individuals, in the modern sense of the word. From then on, painters started to celebrate them: we went from religious figuration, which dominated the history of painting for centuries, to a figuration of the subject, showcasing the personal, the profane. It was the origins of the art of portraiture. The meeting of the sacred and profane.

How have artists apprehended the face over the course of the centuries?

The representation of the face follows the history of techniques. Italian and Flemish painters of the Renaissance were the pioneers in the art of the face. As portraiture became more common, in the second part of the nineteenth century, the invention of photography led to the first artist snapshots, such as that of Baudelaire by Nadar. We moved beyond the bourgeois celebration of the portrait, even if there were still the same codes of seriousness and solemnity. The smile was practically absent from faces until the 1920s.

The start of the Roaring Twenties also marks the democratization of photography. In the US, Kodak developed a small, accessible camera, and with it a powerful archetype to convince Americans to capture their daily life, above all special occasions. It was the period in which the smile became widespread. The face then comes to inhabit a form of memory and souvenir through the snapshot. From then on, the faces that were shot were serene, radiant.

What is happening today with the proliferation of faces in the era of the selfie and social networks?

We have moved from a society of individuals to a society that is hyperindividualized, where we ceaselessly scrutinize ourselves in the mirror, but also in the images we take with our cameras and mobiles, on which we post countless versions of our face. With the selfie, we are seeing the dilution of the image of the self. We no longer find there the absolute value that we used to experience, in the presence of Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, for example. There is a profanation of the face, in the sense that it is no longer sacred. It is rarity that endows something with a sacred value.

People talk nowadays about an “Instagram face”. Kim Kardashian would be patient zero. What does this cloning of a digital face, especially through the use of filters, reveal?

Everybody is a looking for their best angle, even if it involves cheating with technological tools. But that has always been the case. In 1969, the US celebrated the first men on the moon and their wives said they could not recognize themselves in the coverage because of the extent to which their image had been modified. It was already imperative to create the perfect image of the American housewife. In the same way, cinema and fashion want to give the most beautiful, the most idealized image of their celebrities. Their faces cannot be ordinary.

Is the face ultimately the final stage of perfection?

Anthropologically, the face is the high point of the body. It is the most elevated, the closest to the sky in a certain sense. There are, moreover, a whole heap of expressions that denigrate the lower parts of the body. We are also living in a society in which faces are left bare, contrary to others where they are concealed. The face is thus the immediate site of mutual recognition.

One cannot help but see the continuation of a very gendered culture in the way the face is observed. We don’t perceive faces of different genders in the same way and there are stereotypes that make women more bodily than men. She is judged according to the kind of seduction she incarnates, in which the face is central. Culturally, socially, historically, the faces of women speak for them, although that is gradually changing.

Is it the fate of the contemporary face to be further and further transformed?

The face has always been manipulated, staged. Today, we have many ways of modifying it; there are no longer any norms. There is an explosion of different modalities for staging the face and hair. Technology, cosmetic surgery, tattooing and piercing are so many physical and decorative transformations as a result of which representations of the face are evolving.

Why are we afraid of looking too closely at our own faces?

The face is the closest we get to the other. We have the privilege of seeing other people’s, but never our own. We need the mediation of a tool to see our own reflection and that creates an effect of strangeness. Each of us has a bit of an ambiguous relationship with ourself; the confrontation with the face is an enigma. It calls into question our deepest identity. Many people, moreover, cannot bear to look at themselves. The fact that we photograph ourselves incessantly demonstrates that there is something which always escapes us.

What is the future of the face in our hyperindividualized, screen-based societies?

The face is the object of constant polemics. In a certain number of societies, women do not have the right to have a face. The individual is disqualified. But in our hyper-individualized societies, the face can look forward to a happy future, and will not cease being valorized despite a quasi-industrial process of cloning and reproduction. It remains the basic index of one’s presence in the world and the singularity of the subject in a society where everybody passionately, sometimes desperately, wants to affirm their existence. Paradoxically, a society of the hyper-individual means each of us loses a bit of our value.