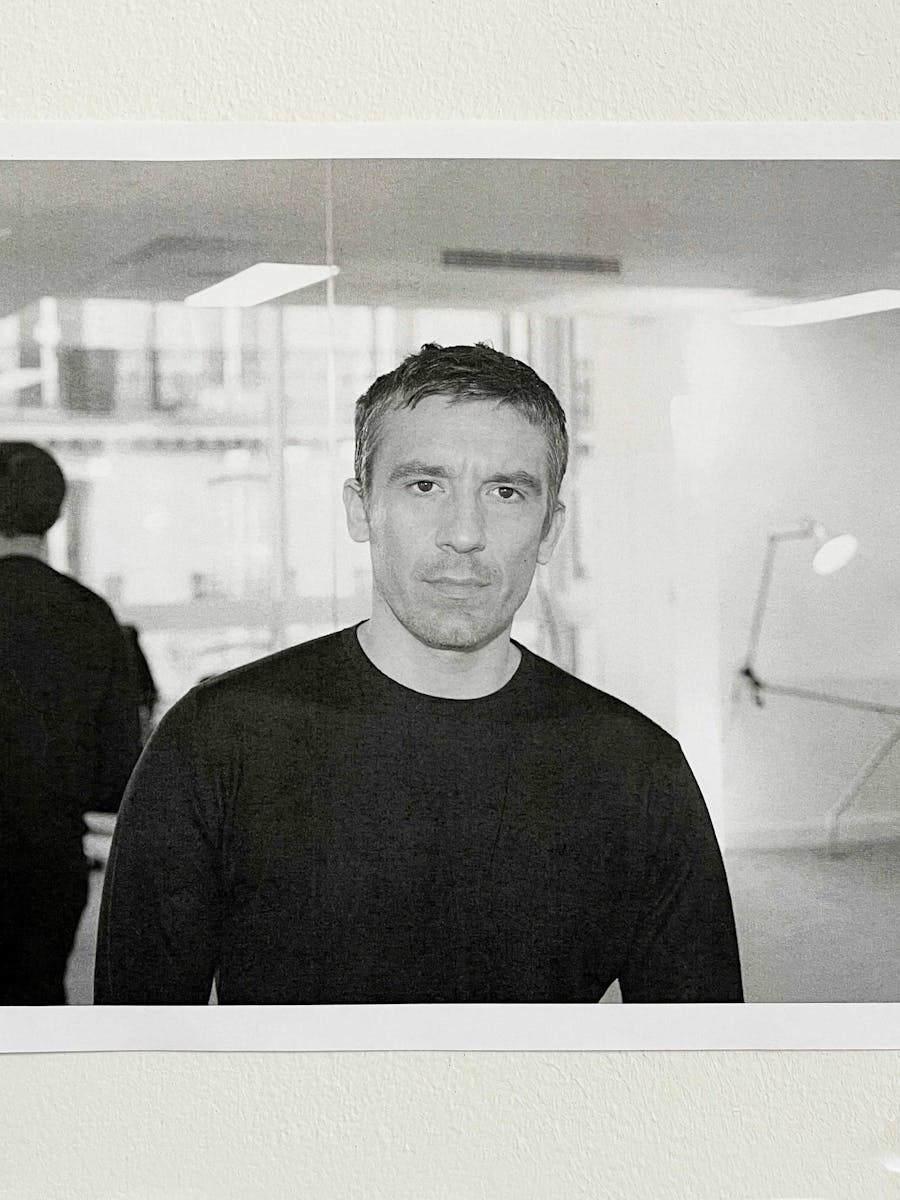

“How do we know if what we’re observing is reality? I often ask myself this question: if I see something in a given form, is it possible that another person is seeing the same thing differently? After all, what I am seeing has already been analysed by my brain, which contains algorithms which have been developed from birth onwards, and are therefore potentially biased [...] Our observation itself can be false, since what we think we see is not the thing itself, in its reality.” These are the words of Aurélie Jean, author of the essay The Other Side of the Machine: A Scientist’s Travels in the Land of Algorithms (published by Editions de L’Observatoire, January 2020). Suddenly things don’t seem so certain. What do we see when we look at a work of art? How do we look at it? With what eyes do we perceive it? Do we see the same thing as the person who created it, or do we just see what we want to see? With a few movements of his pencil, Felipe Oliveira Baptista, artist, creative director at Kenzo, projects us elsewhere. He even leaves open to us the possibility of looking sideways, outside the frame, further, beyond... His naked bodies (quite the change for a fashion designer who imagines all-enveloping clothes, as protective as cocoons) are in the process of coming into being: they contain within themselves the entire field of the possible.

When we gave you carte blanche to explore the theme of the imagination, what was the first thing that came to mind?

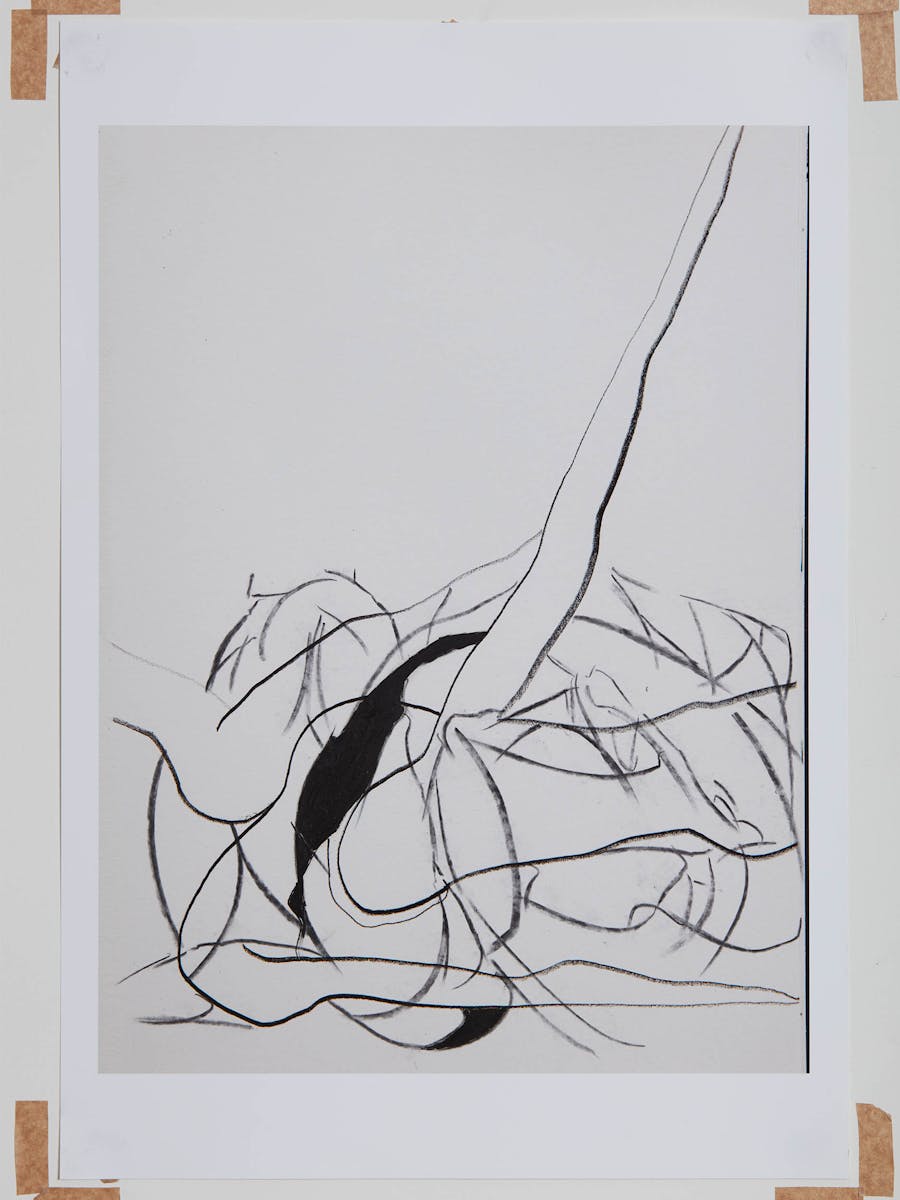

⏤ Instinct: for me it goes hand in hand with the imagination. I place great faith in intuition and I try and protect it as much as possible. In my work as creative director and designer, I am used to putting my imagination to work, using everything it contains. When I draw, it’s different, it’s much more instinctive, wilder. To make the most of the carte blanche you gave me, I immediately thought of producing drawings.

Is drawing a refuge for you?

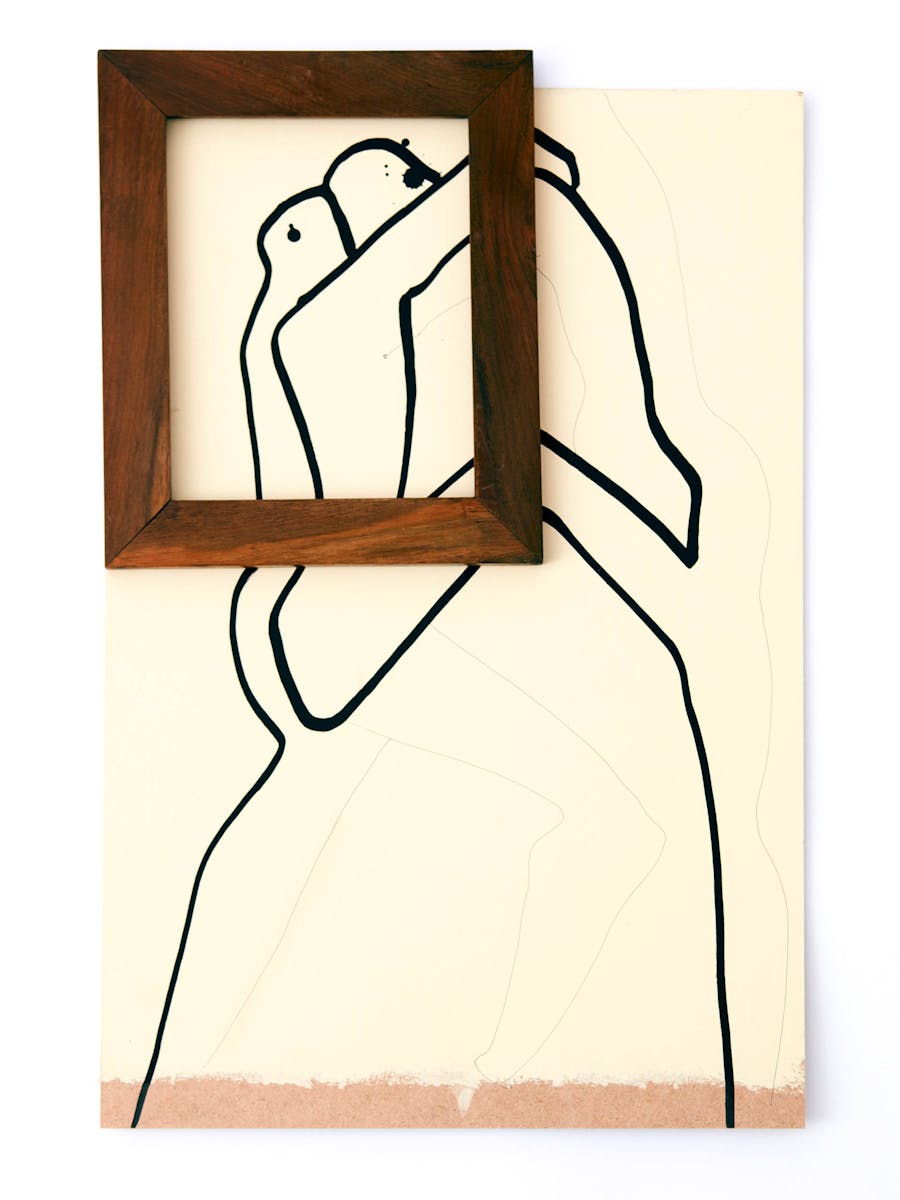

⏤ During the lockdown, I drew a lot, it was like breathing. It’s something I do when I’m well, but also when I feel less well. Not being able to go out, I used what I had to hand; for example, I drew on the insides of doors and wardrobes. My imagination is in dialogue with what I see, what I touch. But imagination is also taking something and looking at it differently, taking interest in a story and decontextualizing it, making it other. That’s why I used the frames that I positioned on top of the drawings, as a metaphor for that idea: there are stories within stories if you look closely enough.

In doing that you offer us the chance to look at what is outside the frame, outside our field of vision, to look at what we normally have to imagine…

⏤ Everyone can look where they want to, how they want to, and interpret things as they want to. What I love about drawing is that I don’t need to explain anything; I just draw what comes out of me. It’s a very free gesture which happens without captioning or justification. Imagination is also the freedom of having protected spaces, free spaces that are purely one’s own. We owe it to ourselves to look after them and nourish them.

Do you have secret gardens, interior worlds which you in fact choose not to explore in your creative work, to keep for you and you alone? Spaces marked ‘keep out’?

⏤ I think that my drawings and photos represent the most personal part of my creative work. There is a part that I don’t show, which is too intimate. I never reveal the things I find most beautiful, or that I think work best. But it’s also wonderful to do things for oneself. I also love drawing in the sand and the idea that the sea will wash it away. Especially nowadays: everything is recorded, scrutinized, analysed all the time. I enjoy that specific form of pleasure and the fact that I’m doing it for free. For me, drawings are a sliver of freedom. I’m not working to a deadline when I draw, I don’t have any goal, I don’t sell them... all that’s important to me.

How do you escape reality?

⏤ There aren’t really any rules. I pay attention to everything and especially to things nobody else is looking at. In general, I pay heed to the barometer of my imagination, I try to keep it in good shape. When I’m too stressed because of deadlines, I am aware that it can seize up. That’s why even when I’m working hard I always try to draw or take photos, to do something a bit tangential to escape from the corridors of habit.

Were you a contemplative child? Were you given to day-dreaming?

⏤ My mother used to say that I could spend hours and hours playing by myself, which doesn’t mean that I wasn’t happy with other people, but I was also in my own world. I spent my summers in the Azores with my grandmother who had a big house and a garden next to the sea. I would go out in the morning and come back in the evening with the dogs, walking over the pebbles. I always felt at peace with my imagination; it was like a companion – more than that even, like my best friend.

The bodies you are drawing are naked, as if liberated from everything and free to become anything…

⏤ I draw a lot of naked bodies – paradoxically since my job is dressing and protecting them! But here the body is at its most beautiful and purest. And besides, it’s not the habit that makes the monk...

There are also your words: ‘Drawing the sound of the sea’ or ‘Painting the soul of the sun’, which act as a springboard for projection. There we also see the power of words…

⏤ I have always had an enormous admiration for the craft of writing and the evocative power of words. In poetry, in literature, words take us places. In my sketch books, there are always words. Those phrases are things that I’d like to do but which I can’t realise. In the end, I get closest to them with a slightly absurd description.

Do you have a ‘real’ refuge you can escape to?

⏤ For the last seven years I’ve been going to Brazil every year, to the middle of nowhere. There, I am in a state of perfect equilibrium with nature. We buy all of our provisions beforehand, because once you’re there you can’t buy anything except fresh fish from the village. It’s great because you really feel as if time has stopped. Being without an internet connection, without being able to buy anything, evokes a lot of memories for me, of the world in which I grew up. I offer my children that experience of wildness and freedom I had in the Azores when I was little. Travelling nourishes our imagination, takes us out of our routines, out of our perceptions of ourselves. In our daily lives we are closed off from a huge number of things.

Entitled ‘Going Places’, your first collection for Kenzo is about travel, about ‘travelling through the world in your stay-at-home clothes’. Running through it is that motif of the stationary journey, as if we can escape mentally?

⏤ Yes, absolutely. I love looking at old photos and telling myself stories...and evoking possibilities. When I was very little, I wanted to make films, that was my first ambition. My work as a fashion designer involves a lot of storytelling. I have always used fashion to nourish myself, to learn things, to move towards areas that interest me and then to escape. Creating is also about aligning horizons, forging connections between things that have no a priori relationship. It’s bringing a new gaze to bear on things, to bring them to new life, because everything’s already been done.

Do you manage to enter easily into the imaginary worlds of others?

⏤ Yes, I think that we are all inspired and moved by other artists, musicians, film-makers... I have very eclectic tastes and references. We all inspire each other, and that is the power and the beauty of art and creativity. We project ourselves not only into the imaginations of others, but also into their histories and their points of view. I collect photo books, I have them all around my house, it’s a way of entering into other worlds. Somehow the lockdown has enabled me to look at things differently. Not being able to travel, for example, has had an enormous effect on our creative processes, but at the end of the day I am inspired by these changes. It’s possible for us to rethink our formulas, our ways of doing things. The mere fact of examining that interests me. Travelling had become like a tic, an easy way of leaving behind the everyday. It’s interesting to think about different ways we can come out of our reflexes, our conditioning. To keep calling yourself into question is to know yourself. We should always be able to ask ourselves: am I becoming normative? Calling yourself into question is an ongoing work.

Translated into English by Sara & Emma Bielecki.