At the age of 34, British designer Craig Green is one of the most promising talents in men’s fashion. Since its creation in 2012, his eponymous label has garnered countless successes. Both experimental and commercial, Craig Green fashion explores ideas surrounding protection and vulnerability, reinterpreting, with an artist’s obstinacy, clothing as uniform. Born in 1986 in Hendon, North London, Green’s father was a plumber and his mother a nurse, but he saw himself more as a sculptor or painter. Ultimately, however, it was in fashion that he found his calling. Mentored by Louise Wilson (whom he always mentions in interviews) at Central Saint Martins, he cut his teeth interning for Walter Van Beirendonck and Henrik Vibskov. As soon as he graduated, he started to make a name for himself on the London catwalks. His first show hit the fashion headlines: “Why everyone was crying at the Craig Green show”, pondered Dazed and Confused in 2014. Never literal, often strange, Craig Green designs call out to you. His fashion has no need to bedeck itself with slogans nor to commit to social causes to justify its existence.

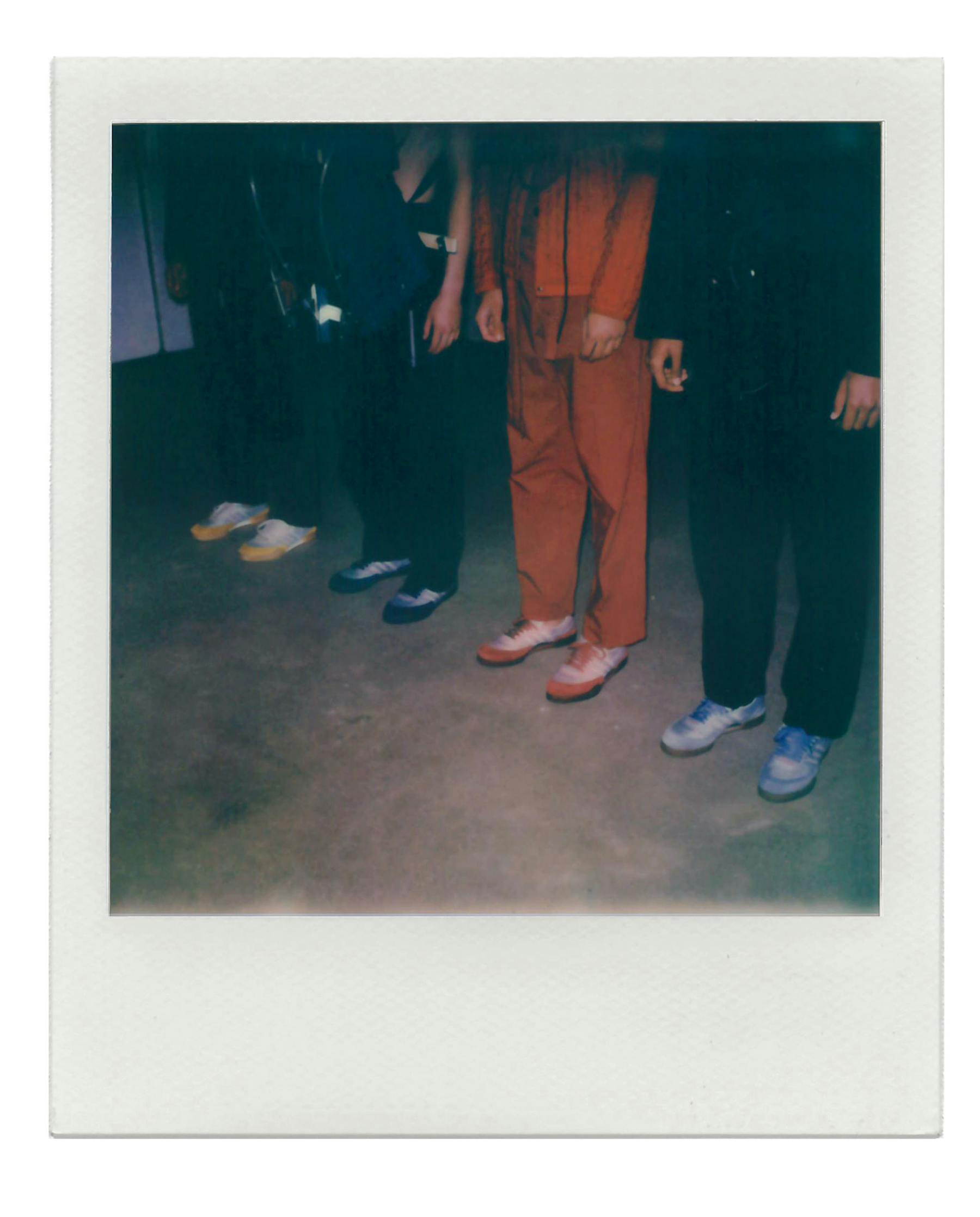

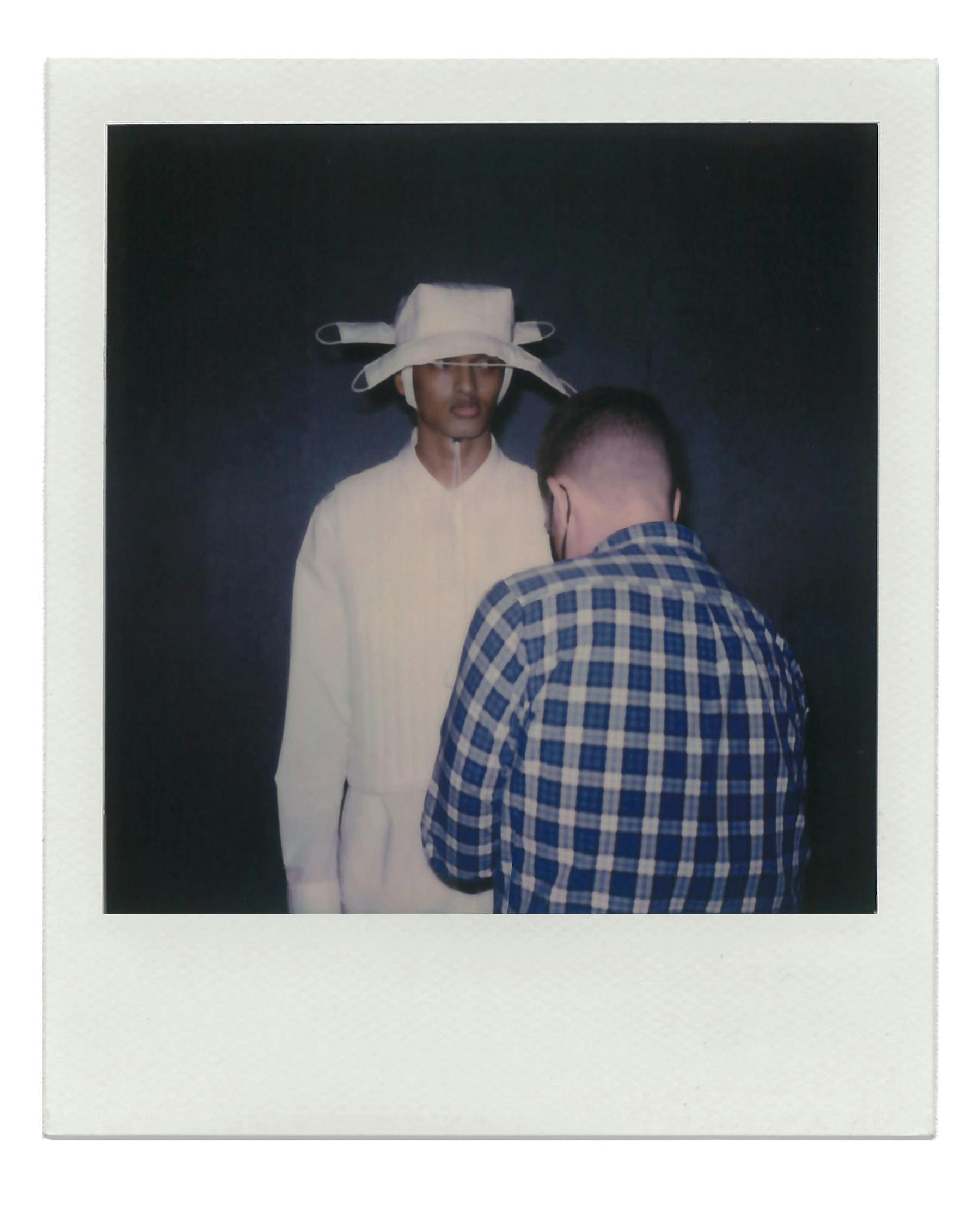

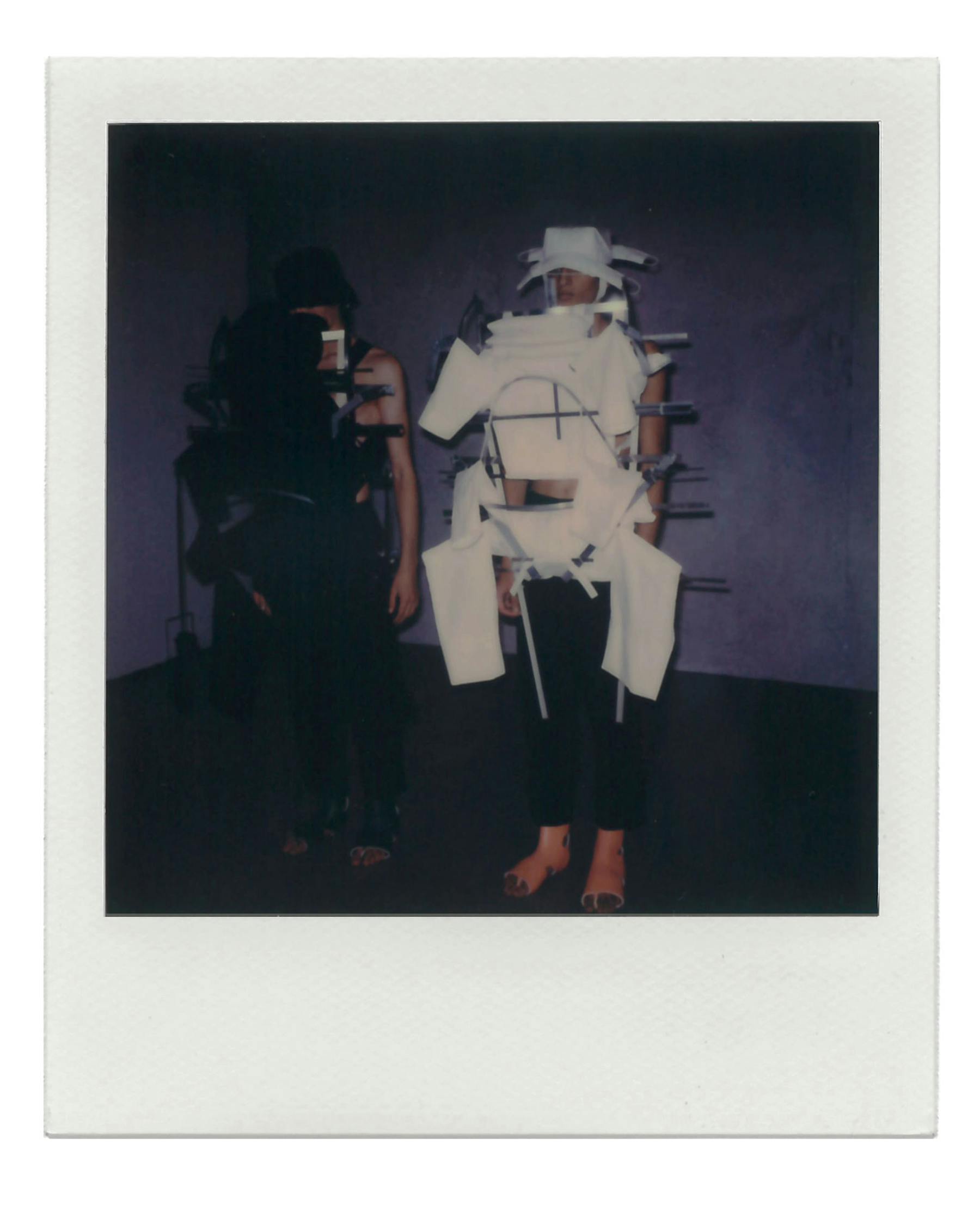

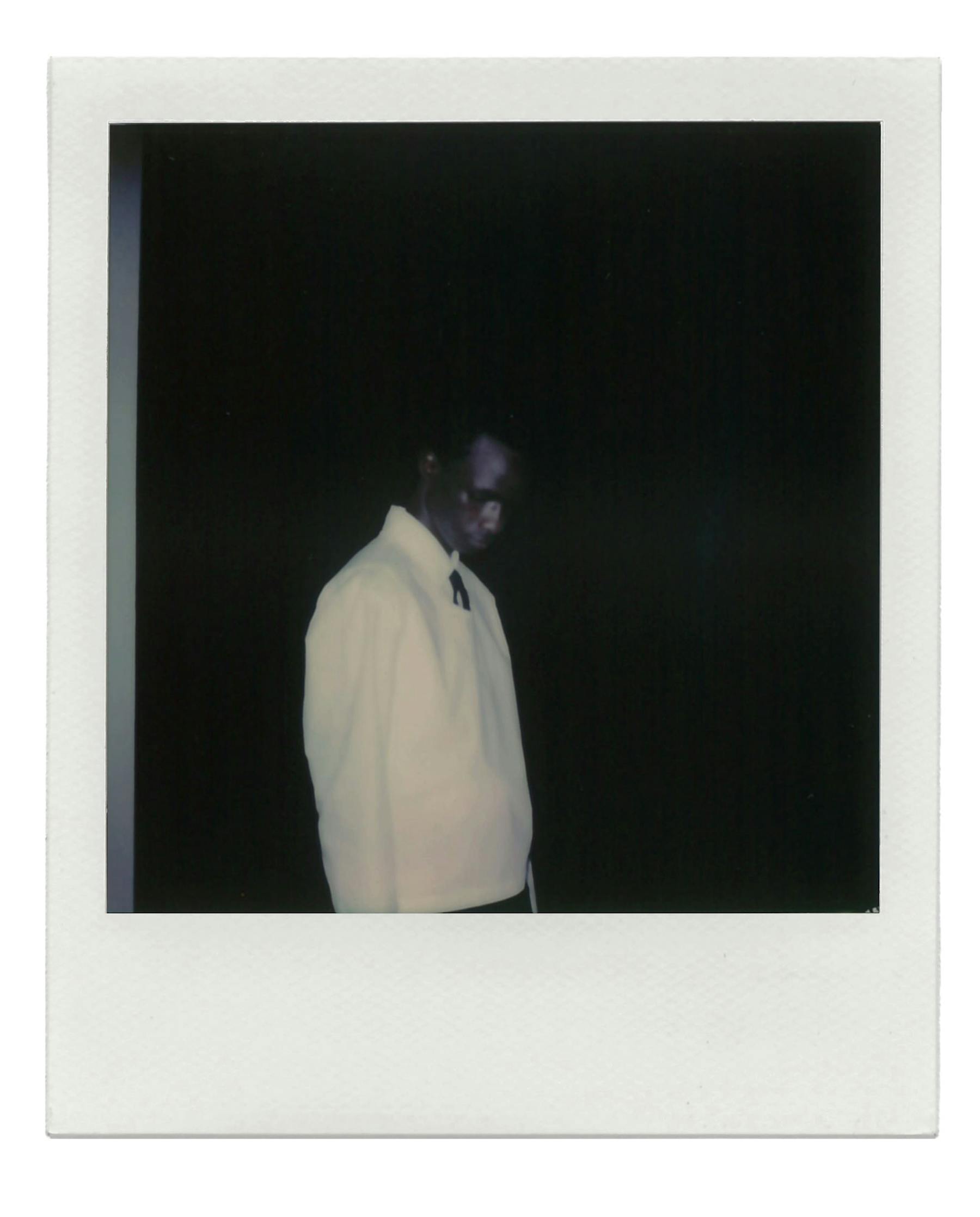

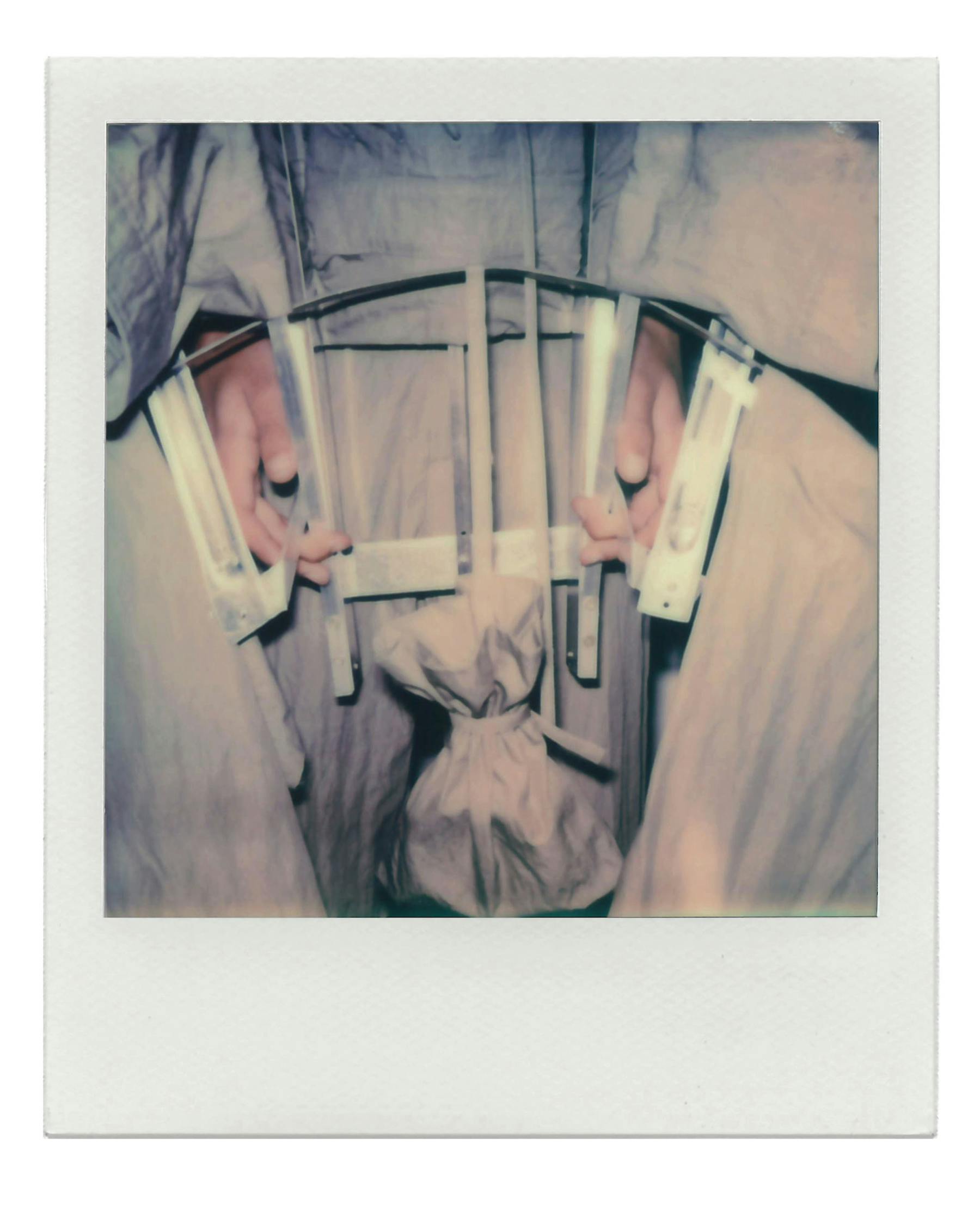

⏤ Since 2017, his highly experimental designs for Moncler (in the context of the Genius project of the down jacket brand) - incredible pillowy sculptures conceived as habitats in and of themselves - have caused a sensation, consolidating his reputation as an artist-designer. On the occasion of his Spring/Summer 2021 collection, a series of Polaroids was shot backstage, a selection of which has been entrusted exclusively to Exhibition Magazine. Designed during the 2020 lockdown, the architectural pieces question the boundary between (science-)fiction and reality, ideas of intimacy and comfort in the age of working from home (for the first time the models are wearing ties!) and underline, like a leitmotif, the importance of the collective. There is innocence here, too. The models are crowned with metallic hats which call to mind mobiles for babies. Because, for Craig Green, clothes are there first and foremost to protect us.

Uncompromising experimentation is at the heart of this issue of Exhibition Magazine, so we thought of you, of course, because you embody the idea of risk-taking. But, first of all, what has this pandemic taught you?

⏤ I learnt a lot about my brand: what we wanted to say, to do and what’s important for us, going forward. I know it’s hard to make plans at the moment, in such an uncertain world, but I think you have to stay positive for the future and hope things will go back to a version of what we had previously. When lockdown happened in March 2020, I had this urge to go to the studio on my own and to just make patterns and start sewing. Maybe it was some form of therapy for me! (Laughter.) I found it important to make things. I wasn’t really sure what I was making them for, since we didn’t know when we would next be presenting something or showing something, but I knew that it was important for me to make. And I guess that’s the reason why I got into fashion in the first place. So, in that way, it was kind of nice.

Have the events of 2020 changed your creative process?

⏤ During 2020, the way we worked was very, very different. We had to communicate in different ways, because as a studio and team we’re very hands on in our process. It really relies on us being together and doing fittings and making things. We’re a very crafty studio. We experiment a lot, so we have had to find a completely different way of making things. The main challenge for us was not being together. I think fashion design and all the creative industries in general rely on the idea of community.

Are the current circumstances stimulating your imagination, or is it, in fact, hard to find inspiration in these dystopian and uncertain times?

⏤ I think you can find inspiration in any kind of situation. When I usually start a collection, it’s very much based around a kind of escapist or fantasy feeling. At the very beginning of the lockdown, I found that quite difficult because I don’t really know what the fantasy is. We’re living in such strange times. I kept going back to things that I found very real, in a way. I thought I was fantasizing about real life because it was something that was so alien at that moment. So we twisted the inspiration. Reality felt like escapism. At first, I wasn’t sure if it was me being inspired or if it was like, “God, I’m so uninspired, I keep thinking of reality !”

The new fantasy now is reality…

⏤ Yes, exactly. Previously we’d always worked with ideas of obscuring the body, covering the face or having that anonymous feeling. But it felt like the biggest fantasy was to see the face again and to see the humanity of the models and the people… We weren’t really seeing people very much. I guess that relates to the way we interact with our clothing now. It feels very different to what it was. We’re dressing, somehow, not to be seen by people. We’re dressing for ourselves and it’s a different intimacy with clothing to what we had previously.

Indeed our intimacy with clothing in this age of working at home has changed a lot. How we dress now is really for our own comfort and pleasure. How does this impact your creations?

⏤ I was really obsessing with the way that things were made and how they felt in your hand and on your body. At the time I wasn’t sure why I was obsessing so much about those kind of things, but I guess that links back directly to the idea of reality. I think the way we interact with our clothing is something that feels interesting again, which previously maybe wasn’t that interesting. It wasn’t the main reason for choosing the clothing we were wearing. So, in some way, it’s kind of a positive thing in a strange way. I like those rules you have around getting dressed. Like when I was working from home, in order to work, I would put my shoes on, even though I wasn’t going anywhere, but it made me feel like I was ready to do something. There’s like a ceremony or a process of clothing yourself, which makes you feel a certain way. I guess you don’t really lose that, even if you’re working from home.

Speaking of this age of working from home, you’ve put black ties on your Spring/Summer 2021 silhouettes !

⏤ Yes, it’s strange because ties are something we’d never really done previously. And actually, they weren’t even ties. We were doing a fitting and there was a piece of fabric on the floor and we tied it around a model’s neck, and someone said in the fitting: “Oh now it’s feels finished!” and I thought “Why does it now feel finished? We’ve only knotted a piece of fabric onto somebody’s head!” This made me start thinking about the symbolism we put into certain pieces of clothing. We saw it as a fabric ribbon, but the way it’s worn on the body completely changes how you perceive it. We’re interested in things like talismans, things we believe have power.

What do you mean by “talisman” clothes?

⏤ It’s the idea of putting so much belief into an object that you think it’s going to save you or protect you from something, which is such a strange idea. And I think that also links to the way people feel about clothing or brands. They feel it will protect them.

The notion of protection is very important to your work. Metaphorically we can read into this in many ways: there is the idea of protecting ourselves from the gaze of the other, protecting ourselves from the hostility of the world, of the unknown, a metaphor for our psychic and physical vulnerability…Would you be able to tell us why protection is one of your leitmotifs?

⏤ Protection really describes exactly everything the brand is about. We always think about uniforms but in a protective way because it links to belonging to something. I think people think negatively of uniforms, as they want to have their own personal identity, which is great. But, I think people want to be part of something as well. And to be part of a group or a community is a form of protection in a way. I always link it back to school uniforms. When I was at school everyone would wear a uniform, even though we were all trying to rebel against it. We always wanted to wear our own shoes or our own items to express ourselves. But, if I think back, it had that feeling of everybody being judged on a level playing field. You weren’t judging people by how rich their parents were. You were just meeting the individual, and, in that way, I think uniforms can be a positive thing. There’s a strange need for protection that we all have. And I always speak about it in a way that you buy clothing that has the potential to do something, even though you’re never going to use it in that way. Like buying an Arctic jacket or clothing for climbing a mountain, though there’s no chance of you ever climbing a mountain, but you feel like you need that level of protection. It’s like buying things from a brand to make you feel calmer.

Experimentation is at the heart of your creations.

⏤ We call everything into question: we constantly experiment. In my studio in London, everyone is a maker. And we want to push the factories we’re working with to a point where they can no longer be pushed. That’s always the way we work.

Going back to the SS21 collection, you did metal headpieces. Do they symbolise something in particular?

⏤ I liked the way that metal head mobiles changed the focus on the model’s face for the first time. It was almost like they were framing the face, but also changing the way they looked because there were metal balls in front of their eyes. And I liked the idea that the metal balls in front of their eyes are almost like a mirror. So, the model can only see themselves and you can see them in their eyes. They had this slightly sinister, calming feeling about them. I guess they were almost childlike, like what a baby has above their cot. I liked the fact that they felt different for the wearer and different for the person looking at it. They had a strange, dark-but-light feeling about them. I think you could look at them in a positive way. It made the models look like they had bright eyes, looking ahead to the future. But also, you could think they looked almost dead behind the eyes. It depends if you have a dark or innocent mind !

How you preserve your imagination? Do you manage to cut yourself off from the never-ending flow of information, from social media or news sources?

⏤ I think sometimes seeing too much and knowing too much is such a negative thing because you lose focus and clarity about what it is you’re meant to do. Even sometimes just making and doing things can really generate ideas in a much better way than only research. We do a lot of research but really when we’re making the garments they change and they adapt. Louise Wilson, who used to teach us at Central Saint Martins when I was on my MA degree, would say: “if you can draw something it usually means that you’ve seen it before and sometimes it’s better to make.” Sometimes we need to see a garment on a body and then start changing it. And then that feeling of being afraid of what we’re making is good. One morning we think it’s rubbish, we throw it in the bin but the next day we take it out the bin and we think it’s amazing, but we’re still not sure about it, even at the moment it’s finished. That feeling of uncertainty is usually a good sign. I’ve always tried to keep that energy as part of what we do.

Do you miss runway shows?

⏤ Yes, in a way. Maybe it’s a bit traditionalist or old fashioned but I think a runway show is such an important aspect. I don’t think there’s anything that can replace it because there’s a ceremony to it. It’s like people coming together to see something. And I think you can’t really replicate that in another way. There’s an emotional aspect to it. It’s the reason why I wanted to do fashion when I was at college. Because originally, I wanted to do painting or sculpture. I went to a fashion show when I was a student and I remember the energy in the room and the energy of the people outside and there was just so much excitement. My heart was beating out of my chest. Of course, there’s new and exciting ways to show collections but I don’t think you can ever really replace a show. But I think the reason I love fashion is the human aspect of it. That’s why I think it’s different to art, because you’re dressing the human body.

The sense of community is also central to your work.

⏤ Yes and I think that’s another reason why I love uniforms and workwear. There’s not really many workforces and subcultures that are left, so I have that romantic idea of uniforms and being part of a community. That’s always been important to me because of the way that I grew up.

You were a boy scout, weren’t you?

⏤ Yes and my mum was a guide leader – the girl version of the boy scouts. I always grew up with people that made things with their hands. I think that’s another important aspect of the way we work with uniform. It’s always based on the uniforms of the people that work, rather than then people who wear them for status.

Do constraints boost your creativity?

⏤ I’ve always said that limitation is the key to creativity. Sometimes I think the worst thing to say to someone is “You can do whatever you want.” In the end you end up hitting a wall because there’s just too many options ! I always go back to the way we worked at the beginning: we didn’t have much of a team, we didn’t have many materials, we didn’t have factories. We just had two fabrics. And it was like, “What can you do with these fabrics that is exciting?” There are so many possibilities even in the simplest things. I think limitation is good. It's a positive thing but that’s probably a negative thing to say! But it’s the most interesting way of working.

Could you tell us about your creative process. How do you begin a collection?

⏤ It changes from season to season but a lot of the time it’s based around fabrics. It’s always about researching and experimenting with the possibility within those fabrics. It sounds strange, but it starts with an emotion in some way. We usually analyse the catwalk show before, and we think: “Now that you’ve seen that, what do you want to see next?” It’s usually a discussion between me and the team about what feels like the next part of the story. At the beginning, our research is very wide and very broad – we don’t necessarily know where it’s going to end! (Laughter.) But that’s part of the excitement! Sometimes things don’t work out, sometimes ideas get put in the “to be confirmed” box for next time. It’s important to have that kind of openness to question everything, to push everything.

Experimentation is at the heart of your creations.

⏤ We call everything into question: we constantly experiment. In my studio in London, everyone is a maker. And we want to push the factories we’re working with to a point where they can no longer be pushed. That’s always the way we work.

Going back to the SS21 collection, you did metal headpieces. Do they symbolise something in particular?

⏤ I liked the way that metal head mobiles changed the focus on the model’s face for the first time. It was almost like they were framing the face, but also changing the way they looked because there were metal balls in front of their eyes. And I liked the idea that the metal balls in front of their eyes are almost like a mirror. So, the model can only see themselves and you can see them in their eyes. They had this slightly sinister, calming feeling about them. I guess they were almost childlike, like what a baby has above their cot. I liked the fact that they felt different for the wearer and different for the person looking at it. They had a strange, dark-but-light feeling about them. I think you could look at them in a positive way. It made the models look like they had bright eyes, looking ahead to the future. But also, you could think they looked almost dead behind the eyes. It depends if you have a dark or innocent mind !

How you preserve your imagination? Do you manage to cut yourself off from the never-ending flow of information, from social media or news sources?

⏤ I think sometimes seeing too much and knowing too much is such a negative thing because you lose focus and clarity about what it is you’re meant to do. Even sometimes just making and doing things can really generate ideas in a much better way than only research. We do a lot of research but really when we’re making the garments they change and they adapt. Louise Wilson, who used to teach us at Central Saint Martins when I was on my MA degree, would say: “if you can draw something it usually means that you’ve seen it before and sometimes it’s better to make.” Sometimes we need to see a garment on a body and then start changing it. And then that feeling of being afraid of what we’re making is good. One morning we think it’s rubbish, we throw it in the bin but the next day we take it out the bin and we think it’s amazing, but we’re still not sure about it, even at the moment it’s finished. That feeling of uncertainty is usually a good sign. I’ve always tried to keep that energy as part of what we do.

Do you miss runway shows?

⏤ Yes, in a way. Maybe it’s a bit traditionalist or old fashioned but I think a runway show is such an important aspect. I don’t think there’s anything that can replace it because there’s a ceremony to it. It’s like people coming together to see something. And I think you can’t really replicate that in another way. There’s an emotional aspect to it. It’s the reason why I wanted to do fashion when I was at college. Because originally, I wanted to do painting or sculpture. I went to a fashion show when I was a student and I remember the energy in the room and the energy of the people outside and there was just so much excitement. My heart was beating out of my chest. Of course, there’s new and exciting ways to show collections but I don’t think you can ever really replace a show. But I think the reason I love fashion is the human aspect of it. That’s why I think it’s different to art, because you’re dressing the human body.

In your view, how has men’s fashion evolved in recent years?

⏤ It’s evolved so much. When I first graduated in 2012, it was the first year that they had the London Men’s Fashion Week. I think people started to see men’s fashion as its own thing. In the last ten years, there’s been a big change in the way that people view men’s fashion and the way that men dress. I think it’s become more acceptable for men to care about the way they dress and look after themselves.

Has Instagram changed your way of designing?

⏤ Even when I was studying, the most important part of fashion, I always thought, was the image-making aspect. The shows that I love from the past are the ones that make imagery that lasts a long time. It links in some way to the world we’re living in now, that image-making aspect. But it hasn’t really changed the way that we design. I know some people talk about designing for Instagram but that’s really not something that we do ! (Laughter.) In one of our shows we had everything on the back of the models for the people at the show to enjoy it. So it wasn’t for the catwalk photos or the social media in a way. It was for the people. Maybe it’s anti-Instagram in that way! (Laughter.)

What constitutes success for you?

⏤ It’s a difficult question. Success for me is being able to do something you love and to be excited to go to work every day. I know so many people who hate their jobs. People think work is work, but work is life ! You spend more time with the people you work with than your friends and family. So, you have to really enjoy what you’re doing, to be able to have a happy life.