From the Unthemed Issue

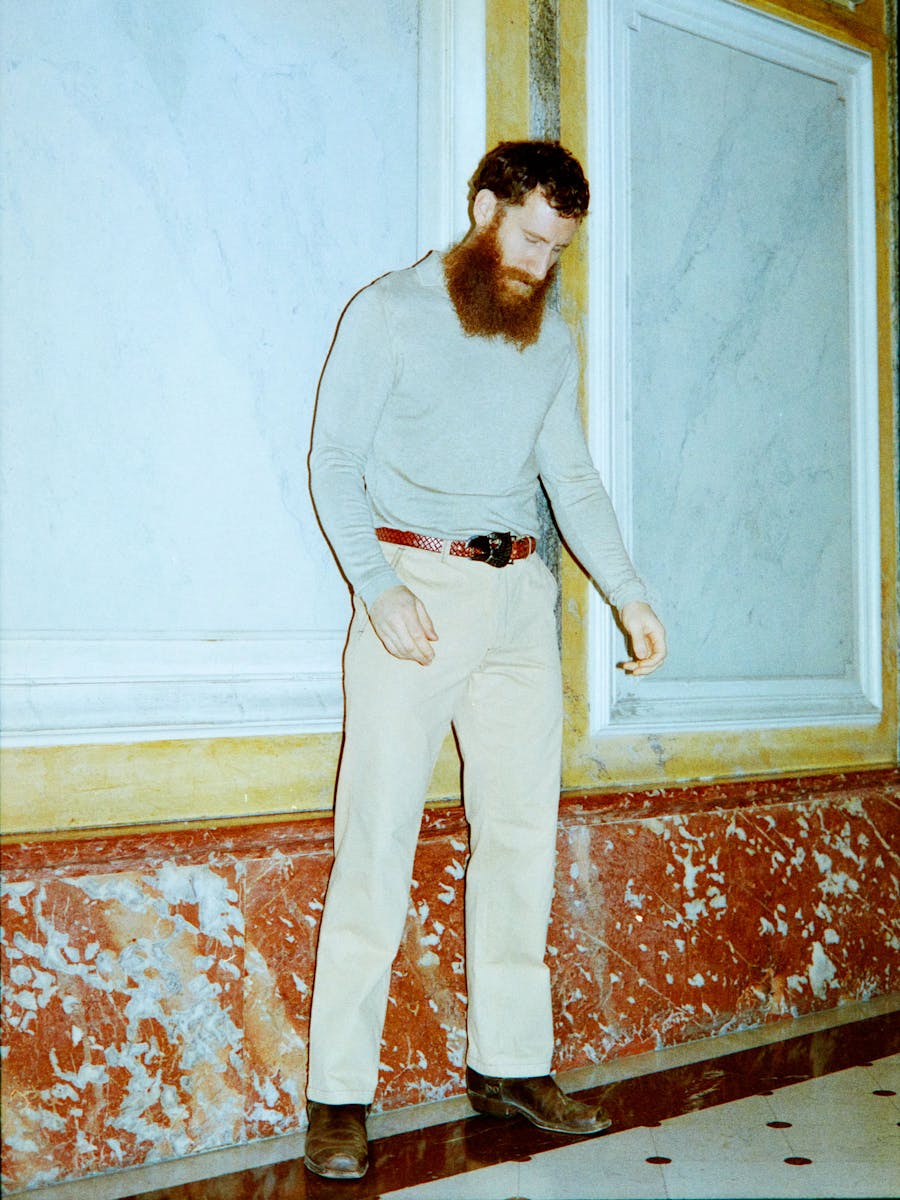

On land, he’s all at sea. But when he’s on stage, he’s walking on air. They say he danc es. But it’s not just dancing; it’s a process of self-abandon, of self-sublimation, of giving himself over to it entirely. His movements pay no heed to convention or genre. They borrow as much from hip hop as from contemporary. Pop culture’s new darling, Léo Walk never ceases to find diverse sources of inspiration. His new piece, Maison d’en face, with his company La Marche Bleue, explores human relationships, relationships which are born and which die, which can be deep or fragile.

How did you catch dance fever?

I started when I was little. As soon as I could stand up and experience movement.

What do you experience physiologically and emotionally when you dance?

It depends. I would say that at this moment, since there’s a lot weighing on my shoulders, my dancing is a lot about weight. I close my eyes a lot and I try to enter into a kind of bodily sensation where I am really looking for imbalance. There’s a contrast between that guy who’s trying to let go of something and the weight which is anchoring him.

So there’s something very cathartic about that?

Exactly.

The body, through dance, is manipulated, defied, disciplined, transcended, maltreated… I imagine that, as a result, dancers have to construct and maintain a very specific relationship with their bodies.

Yes. We can be both hyperconnected to our bodies and hyper-detached. For me there are moments when I look at every part of my body, I go home and massage myself; I really take care of the machine. And there are other moments when, on the contrary, I really feel like I’ve completely exited the machine – I’m no longer in it – as if I’m outside my own body.

Does learning to discipline your body increase self-confidence?

When I dance, yes. When I don’t dance, there are moments when it’s not as easy. But it’s true that when you dance, you feel every inch of your body and soul.

I interpret the fact that you refuse to let yourself be pigeonholed, mixing breakdancing, classical, contemporary and electro, as a way of laying claim to artistic freedom. Is it essential for you to feel free?

Yes, I think that’s been one of the biggest struggles in my life in general. I rebelled against my parents to become a dancer. I went against my own culture by trying to find something different. Now it’s really open, but five years ago when I was dancing in a battle in Doc Martens, it was tough. It’s an ongoing struggle, and it’s not always easy to shake things up. I still get a lot of abuse online. When you draw a parallel between two cultures, you’re brushing up against deeply rooted issues.

In 2018, you founded your own company, La Marche Bleue, comprising nine dancers. What unites you in terms of philosophy and sensibility?

They’re all completely different. So I’d say it’s really me who unites them. I try to convey my vision of things and in four to five months, they adopt an identity which converges with mine. After, there’s then an opening towards a kind of gentleness and poetry, but not necessarily. I’ve just taken on a dancer in whom I really don’t necessarily see poetry – I see a lot of brutality.

Brutality can be poetic.

Yes, that’s true. I like it when things aren’t all smooth and when there’s a mix of energies.

We’ve seen you in various music videos, in different ads, or opening the Césars 2020 ceremony with La Marche Bleue. Do you feel as if you are participating in the democratisation of dance? Dance is a democratic discipline in and of itself, but as soon as it leaves the urban context, and goes in a more classical or contemporary direction, it’s immediately perceived as more elitist.

In any case, that’s part of what I’ve been struggling with for several years. I’m pretty happy with the direction things have gone in. My initial aim was to beautify hip hop, to make connections between lots of different things. I have this thing where I like to bring things and people together.

Uniting people around dance.

Yes, that’s it. Really uniting. Being able to speak to the intellectuals as much as the people in the council estates. That’s really the hardest challenge.

After your first show in 2020, “Première Ride”, you are currently putting together your new piece with Marche Bleue, “Maison d’en face.” How have your practice and approach evolved between these two projects?

For “Première Ride”, there was no reflective process; I was an open book. And now, it’s a different thing, because I’m more mature. In the first piece, I was saying, "your child’s heart – don’t lose it.” But I feel a little like I have lost it. I’ve bought an apartment. I’ve got a loan. I have to manage tremendous human complexity with my dancers… I’m growing up, in many ways. I think that, as a result, my way of speaking and my writing are going to be a little more mature.

“Maison d’en face” is going to explore romantic relationships and friendship. How do your own feelings influence your creativity?

They go hand in hand and if I try and go against that, it blocks my dancers and my own creative process. You’ve got to listen to yourself. All emotions give you something to work with.

Is pain nourishing for you?

Absolutely. I’ve had a hyper destructive side since I was little. I destroy everything in my relationships – I can’t help it.

And does dance not help you to heal? The fact of having an outlet, a space to express what you’re feeling…

Yes. It helps a lot. The times I’ve been the most stable in my life are the times when I’ve been dancing the most. But as soon as I stop, things get dark.

Everything started for you in the street. Is that a space which continues to inspire you?

I don’t think so. When my story telling was based in the street, that was coming from a place of truth. At 16, I really had to go and dance in a car park, because I didn’t want to wake up my mother and little brother who were sleeping in the same room. I drank vodka to calm myself down and then I danced till three or four in the morning. It was really the street at one point in my life. Today I’m a hipster. I’ve got cash. I don’t want to play at being a roadman when I don’t have that kind of life any more at all.

Do you not miss the energy and the spontaneity of breakdance battles?

Yeah, of course. It’s an energy that I have in me. I always want to keep doing it – and I’m still being asked to judge battles. But I feel that I’ve succeeded today in going towards something which is much more me, where I work more deeply with people I love, in a really beautiful studio. I’ve got to a place I thought it was impossible to get to, in life and in dance.

Beyond dance, you’ve got your own clothing brand – Walk in Paris – and you’ve brought out a mixtape – the Walk Tape. Do you plan to continue to extend your universe to other artistic domains?

I think so, yes. But everything I’ve done in my life, I’ve done to survive. Before starting my brand, my friend and I didn’t know what the hell we were doing with our lives. He was delivering pizzas. I was working with kids. We were sitting on the banks of the Marne with a joint and we said, "listen, let’s start a brand". We were determined. I always do things with intensity. For example, I want to direct. I’ve had an idea for a film for a long time. But there’s not yet that trigger that means I feel in every atom in my body that I have to do it now.

What are you most proud of today?

I’m not a person who’s really proud of things.

Because you’re eternally unsatisfied, or is it because you have difficulty recognising your own worth?

Because I’m a real perfectionist. I can’t stop myself seeing the mistakes that I’ve made and thinking about how to do it better next time. I’m proud when I have a real feeling. That doesn’t happen often, but there are certain moments in the dance. A few seconds where things are suspended. A few seconds of grace; a kind of trance.

“Maison d’en face” by La Marche Bleue is touring from February 2023 and is at the Théâtre de Châtelet in April 2023.