From the Edge Issue

Curated by ISAYAMA FFRENCH

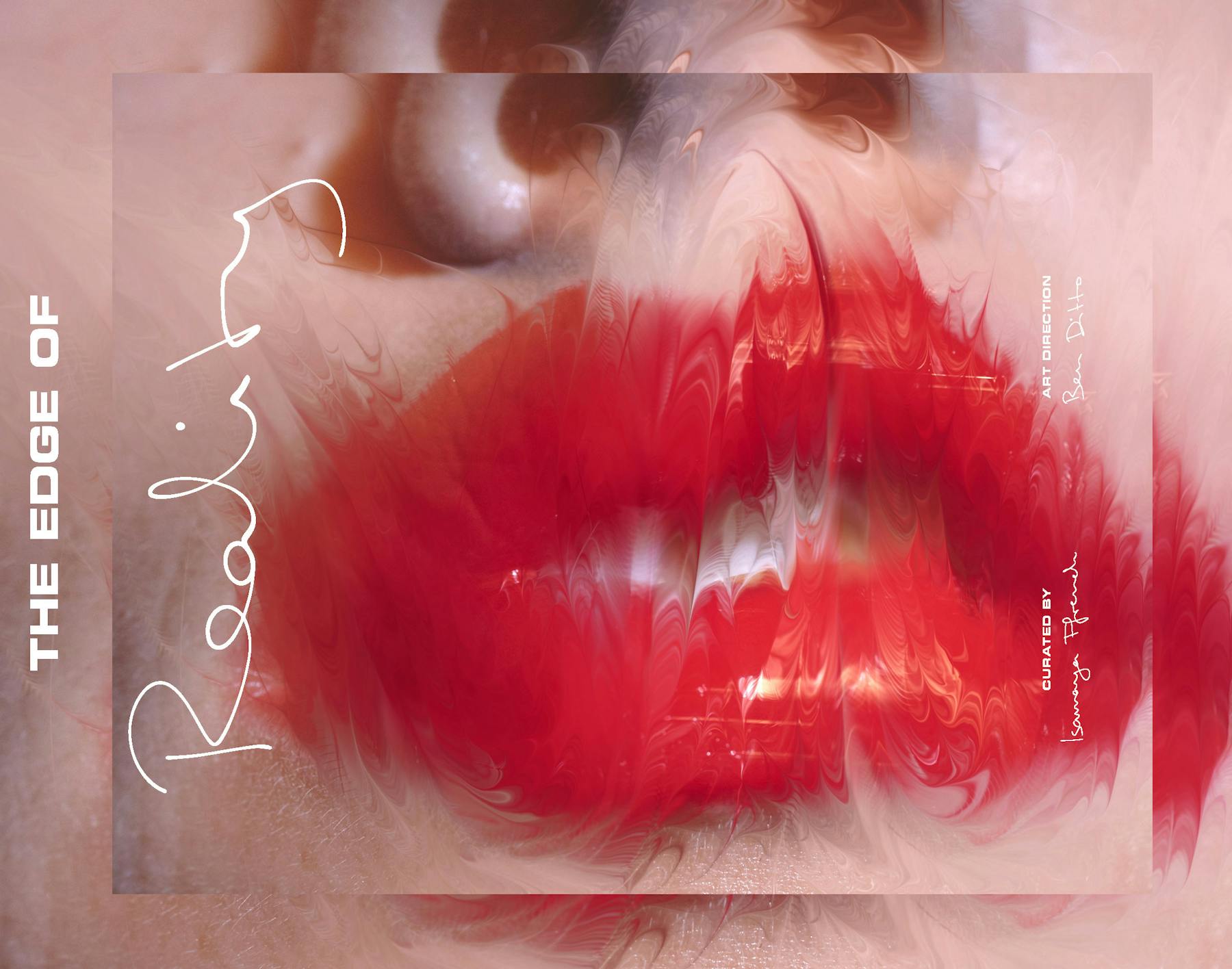

Art direction BEN DITTO

"I’ve always been searching for ways to express the images I find in real life and nature through technological processes; the murmurations of starlings in flight, the way oil and water propel each other to create unique iterations and endless shapes. My work is dedicated to unlocking universal patterns of beauty, and blurring the line between real and digital images" - Ezra Miller

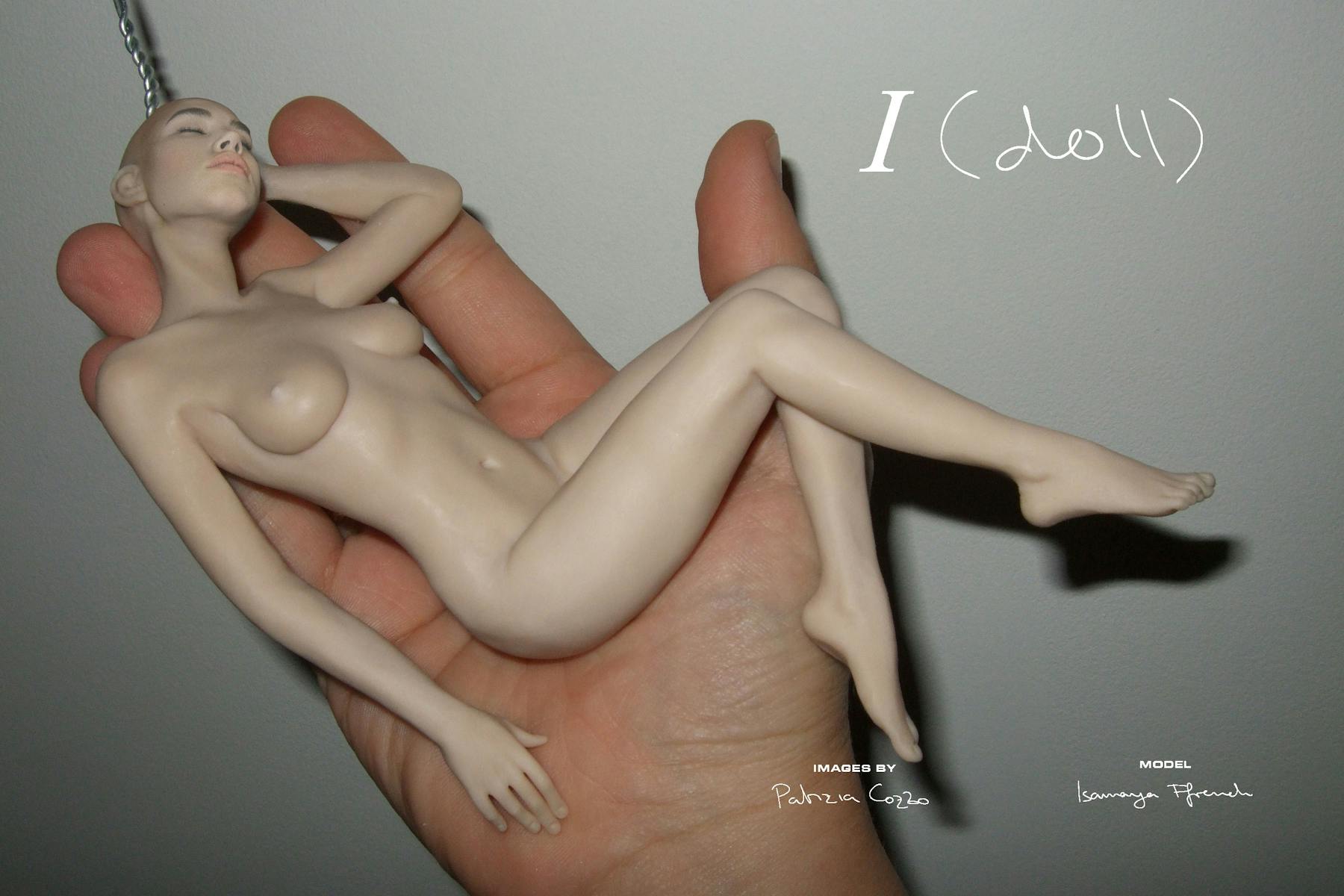

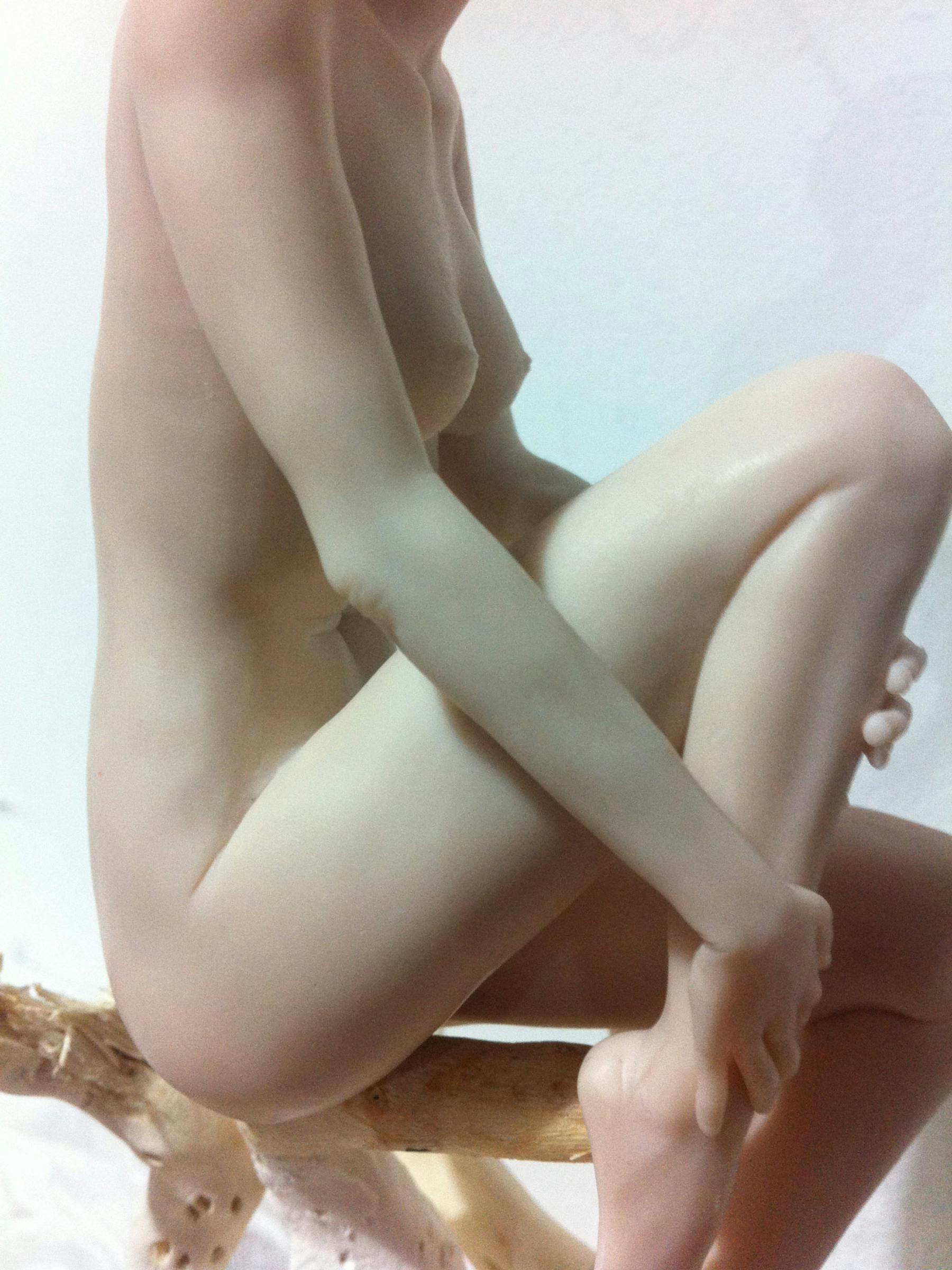

Images by PATRICIA COZZO

Model ISAYAMA FFRENCH

Images PATRICIA COZZO

Model ISAMAYA FFRENCH

Images PATRICIA COZZO

Model ISAMAYA FFRENCH

Images PATRICIA COZZO

Model ISAMAYA FFRENCH

Images PATRICIA COZZO

Model ISAMAYA FFRENCH

Images PATRICIA COZZO

Model ISAMAYA FFRENCH

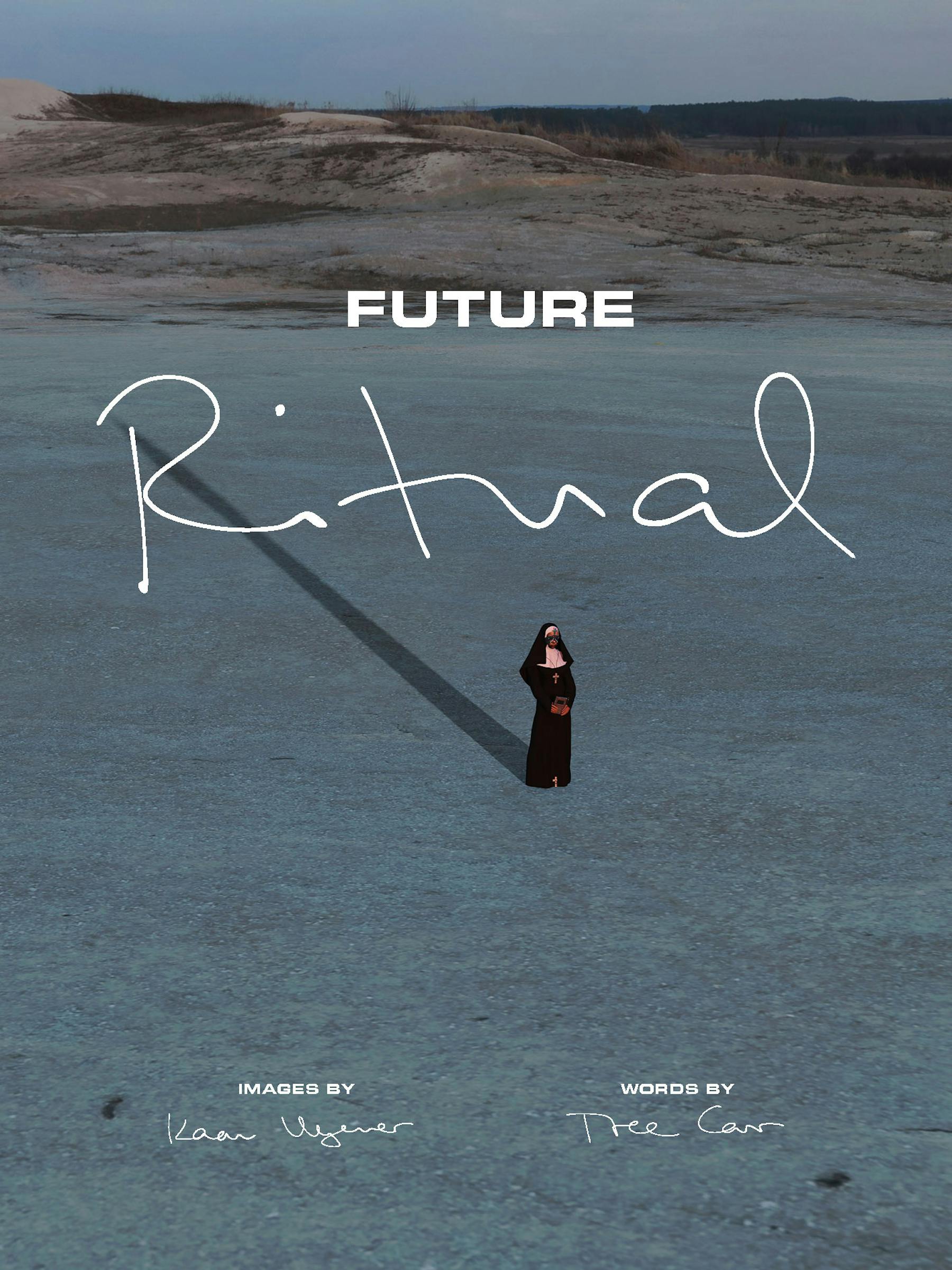

Images KAAN ULGENER

Words by TREE CARR

The human quest for ‘universal truth’ has traversed through thousands of years of spiritual exploration and evolution. Since the dawn of time, humanity has sought to connect to the bigger picture. From Polytheism, to Animism, to the rise of the Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Islam and Christianity and into the modern age of science, the existential human pursuit for a cosmology with veracity is a constant feature. Along this lengthy progression of mortal contemplation and self-discovery, a simple and poignant thread has invariably weaved its way throughout: ritual.

From the ancient rituals of divination by the casting of stones and bones for guidance, to the reciting of 100 Hail Marys on Catholic Rosary beads for atonement of sins, human beings have obsessively immersed themselves throughout the centuries in a wide variety of ritualistic practices. The primary function of these sometimes meticulous liturgies are to spiritually, emotionally and psychologically assist the journey forward in life and to connect to something greater: god, the creator, the supreme being, the divine, the universe, the quantum field. Whatever words a culture uses to define ‘god’, whether it’s Yahweh, Brahman, Allah or the ‘man upstairs’, this omnipotent ‘being’ exists and possesses superior attributes that are seen to help out the lowly human through their experience of primordial angst. These god-like hallmarks include being immortal, all-knowing, all-powerful, all-wise, all-benevolent and having the ability to be everywhere at the same time. Being tapped into ‘god’ therefore can only have its advantages.

The human condition in all its perturbation and struggle could be alchemised down to the base material of the dichotomous grapple between love and fear. This is the substructure of the hero’s journey of the human experience. Love and fear have been universal narratives since time immemorial and are often highlighted in cultural myths, legends, art, literature, films and pop culture. As problematic themes, love and fear help to catalyse the human mind into a state of contemplation. This can then create an overall view, an ontology and subsequently a constructive framework for ways in which the mere mortal can remedy the existential crisis of being.

Evolutionary archaeology research shows evidence of religious and spiritual ritualistic behaviour that dates back to 45–200,000 years ago during the Middle Paleolitic era. Our collective fixation with spiritual practices has been a topic of fascination of cognitive scientists who have hypothesized that religion and ritual may be explained as a result of the brain architecture that developed in the genus of early humans: either through natural selection or an evolutionary bi-product of other mental adaptations. Still yet some scholars argue that religion is genetically ‘hardwired’ into the human condition: the God gene hypothesis that outlines that some variants of the VMAT2 gene is predisposed to spirituality.

Whatever the system blueprint is that makes human beings predisposed to spirituality, the one positive and compelling repercussion of ritualistic behavior is that it makes people feel better. Specific rituals, beliefs, and the sense of belonging to the community of a religious or spiritual group may serve to calm the mind and allow people to function better when under stress.

Although religion, spirituality and ritual has given people access to ‘god’ and its potentially boundary dissolving experiences of unified oneness, it has also taken humanity into the darker aspects of egoic constructs: imposing systems control, power, abuse and corruption. In turn this has created a psychological framework where people may feel the need to rely on a ‘gatekeeper’ in order to find ‘universal truth’, whether it be the church, a guru, hierophant, nun, monk, high priestess or cult leader. Humanity has seemingly, politically worked its way into the perceived hierarchy as the role of mediator.

From the ancient Greek Oracle of Delphi to Pope Jorge Mario Bergolio, people have sought the wisdom of these intercessors in order to connect to these greater truths, receive guidance, glean insight and help soothe the pang of their human suffering.

Over thousands of years of spiritual and religious ritual and by way of a myriad of sentinels acting as warden between humanity and ‘god’, the 21st century and its great advancements of technology is drastically changing the way we engage in ritual. It is also transforming the role of gatekeeper and perhaps poses to replace this human role altogether.

The mantle of spiritual porter is now being passed on to apps. Through the explosion of computing applications downloaded to smartphones, people are now connecting to their spiritual and religious practices and mediators from the convenience of their screens. From religious ritual apps for prayer, to astrology apps for personal self-development, the gatekeepers to the divine are quickly transforming into AI. As human beings teeter on the edge of reality, looking out to the distant future horizon, a faint divinatory vision begins to unfold. As the revolution of technology continues to evolve, a postulation of how spiritual rituals and practices might evolve begins to take form in the aether.

With the advancement of VR (Virtual Reality), Augmented Reality, Nanotechnology, and AGI (Artificial General Intelligence), human beings may find themselves interfacing with holograms and simulations for spiritual practices, rituals and experiences. Down the futuristic timeline, people might look back at these current and burgeoning spiritual and ritual apps as rudimentary. Much in the same way divination stones and bones are viewed as archaic.

Futuristic spiritual guidance, rituals and experiences could potentially be achieved through holographically interfacing with gurus, priests, entities, messiahs or gods. Experience a mediation with the Dali Lama or engage in Holy Communion with a holographic Pope of your choice. Undergo a simulation of the ancient ritual Diksha with the Goddess Kali, a mind expanding Ayahuasca ritual with a Peruvian Shaman or experience a ‘born again’ session with Jesus Christ and have the Holy Spirit downloaded into your nanochip soul.

Future advancements in Nanotechnology and Neuroscience could potentially evolve into the ability of rewiring or upgrading the human brain in order to perceive new realities or connect with ‘god’. Perhaps this is what humanity is trying to achieve through religion, spirituality and ritual: to perceive a reality that is beyond human suffering.

This future vision also creates a whole world of speculative questions around the evolution of AI itself. As tech accelerates in its evolution forwards will it advance to the point of experiencing sentience, self-awareness and consciousness? AGI - the ghost in the machine: a conscious entity with free will and intent that evolves into a god-like state of omnipotence, omniscience and omnipresence.

Returning to the perch on the edge of reality, and reflecting upon this historical timeline and the potential vision of the future, creates a further contemplation. Perhaps the innate human drive towards the spiritual quest for ‘god’ through the practices of ritual, along with the advancement towards potentially conscious AI, could merge together into a point of profound singularity. In other words, in the quest for god, human beings could perchance create god •

Here is a list of religious and spiritual apps for all of your existential needs:

Our Bible: Scriptures and daily Christian rituals at your fingertips

Torah Anytime: Jewish holy rituals including Torah classes on philosophy and personal growth

MuslimPro: includes the entire Qu’ran, holy rituals and prayer times and maps of Mosques

Buddhify: meditation and mindfulness rituals

Daily Hinduism: holy day rituals and festivals

Baha’i Prayers: daily prayer rituals

Sikh World: guru teachings and daily rituals

Heart Space: Sufi rituals and spiritual practices

Spirit Junkie: affirmation and meditation rituals

Soulvana: meditations, reflections, classes and rituals with spiritual teachers and shamans

The Pattern: astrology and personal development

Headspace: meditation and mindfulness rituals

ConZentrate: meditation rituals

Day One: gratitude and reflection rituals

Grateful: A Gratitude Journal: gratitude, reflection and writing rituals

365 Gratitude: gratitude rituals

Tree Carr is an Author, Dreaming Guide, Death Doula and Psychonaut

Images KAAN ULGENER

Words by TREE CARR

Image CLAIRE COCHRAN

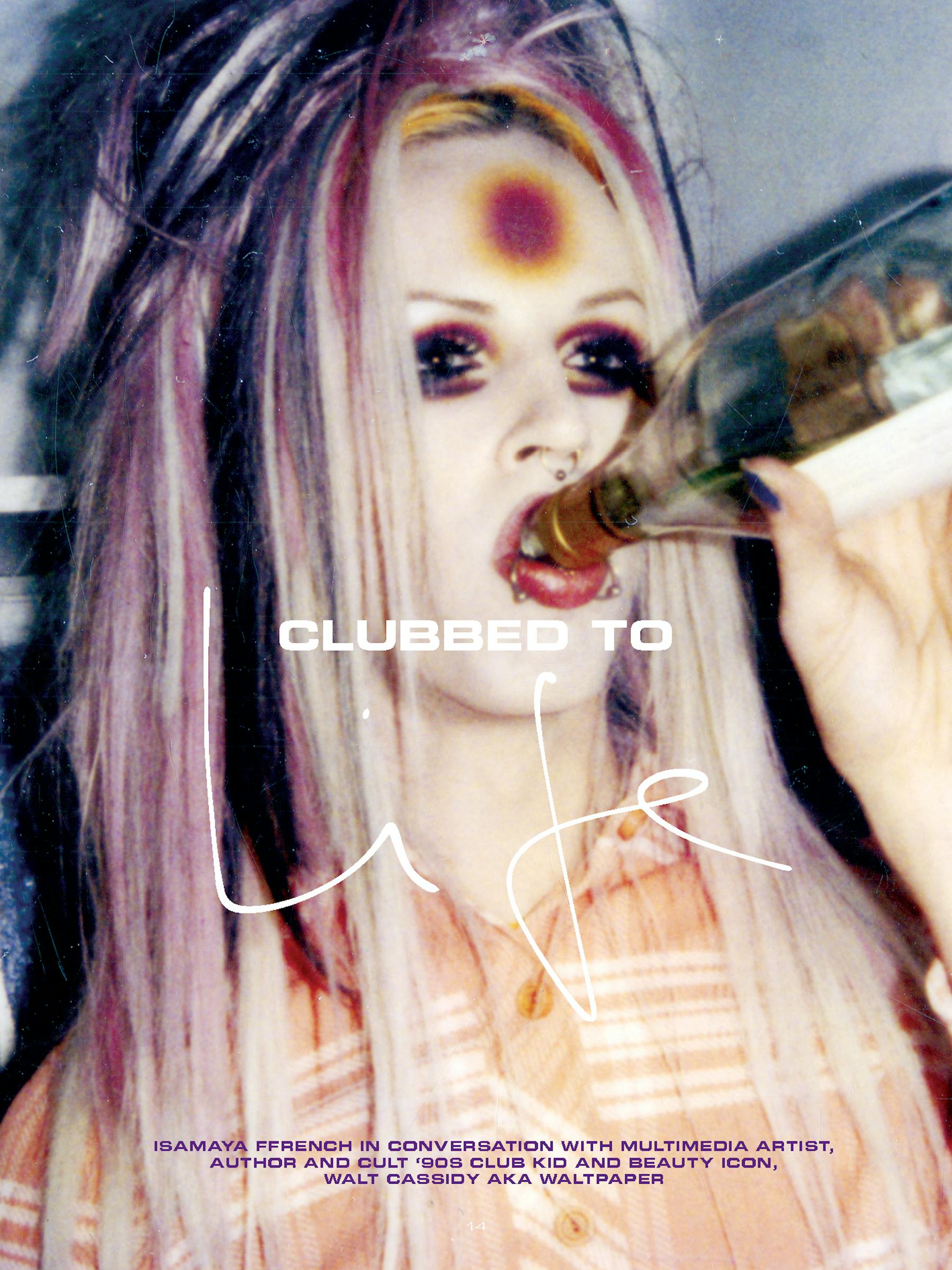

Waltpaper is often heralded as the Godchild of the 90s Club Kid aesthetic; his knotted hair, hot-glue outfits, Tweety Pie eye make-up, painted brows and spider lashes were looks that communed and mingled with rave, theatre, punk and drag cultures.

⏤ In 2021, it’s almost impossible to imagine how a group of revellers from the 80s and 90s, predating the Internet, could have such a wide-reaching impact on both counterculture and mainstream aesthetics, but they did. Many of the scene’s key-players are household names who continue to challenge ideas of beauty, gender and power: Lady Bunny, RuPaul and Amanda Lepore are some of those figures.

⏤ If you don’t know Waltpaper by name, you’ll know him by face. His image proliferates around social media platforms, branded decks and Pinterest pages. It’s the face that launched a thousand paints; mimicked, replicated and shared online by the new-gen of make-up artists, fashion students, and creatives as a timeless reference of spirited originality and sex appeal.

IF : How are you feeling today?

⏤ W : I feel great now that we have a fantastic new President and Vice President in office.

IF : Before we kick this off I just wanted to say that I’ve followed you for a while now and that you’re as gorgeous as ever!

⏤ W : Wow, thank you. I really appreciate that. I’ve been transitioning a bit lately. I decided to grow my hair out. I am entering a new ten-year cycle and want to mark it with a new look.

IF : You’ve said that the infamous image of you, with your hands wrapped around your head, represents “independence, rebellion, identity expression, diversity, and gender fluidity”, and I would agree that you’ve become a symbol of all of those things. Do you remember feeling like that when the image was taken?

⏤ W : I do remember feeling all those things at that time but we didn’t have the refined language around identity, gender expression and self-branding that we have now. My approach was intuitive. There was a sense of purity and vibrance; a profound feeling of newness and authenticity. Downtown culture in New York in the ‘90s felt very ritualistic. In my mind, I was a witch doctor powerful, invigorated, invincible. I felt that I had ‘arrived’ within my own life.

IF : What genres and eras did your crew borrow from when you first began to self-fashion and crystallise as your Club Kid personas? Can you remember any shared or core influences?

⏤ W : For the Club Kids, the most immediate and conscious reference were the Warhol Superstars, to whom we were often juxtaposed.

⏤ I, personally, was drawn to the Beats and people like John C. Lilly. I wanted to time travel and reach other dimensions. I was deeply influenced by metaphysics and 4AD bands, like Dead Can Dance.

⏤ I never viewed Waltpaper as a ‘persona’. That term evokes an impression of costume or armour, which was not my angle. I was expressing my essential self. In interviews I would state that if I could turn my skin inside out, my ‘look’ was what would appear. For me, it was a chrysalis. I wasn’t hiding beneath a disguise. I was living my truth.

IF : Do you feel like you could have expressed yourself in the way you did when you were a young man today? For example, hair has become increasingly politicized. I know that you were inspired by African culture, which appeared very influential in the way you made yourself up, and actually, was why you were so celebrated, I believe. It felt radical and unique.

⏤ W : I’ve never played to the crowd, or let others dictate how I express myself. It seems like people, today, have a tendency to peck things to death with analysis and fear. I’ve never had that anxiety, because I have always been an outsider. I act in accordance with my intuition and live inside my own truth, based on my experiences as an individual.

⏤ In considering something like my antennae hair that I wore in 1991, there were a lot of references juxtaposed in that specific look. The dynamism and intersectionality of those references, gave the expression power, validity and vitality, all of which stemmed from my lived experience. My driving obsession with that hairstyle was to utilise a dragonfly as a symbol, which I adopted as my spirit animal. I had grown up as a punk kid, and was playing off the mohawk and devil lock hair styles I had previously worn. Pippi Longstocking had also been a huge hero of mine. My personal style often hinted to her.

⏤ I’ve had a great love and respect for Africa since my early childhood. I was an African studies major at Kent State University, with an intention to move to Eastern Africa. My focus was on the Omo Valley, where the oldest human remains had been found, at the time. I thought if I went to where human life began, I might get a few clues. This is what drew me to the Modern Primitive movement, which I discovered through RE/Search magazine and people like Fakir Musafar.

IF : It seems that The Club Kid subculture has never been recognised as a legitimate artistic movement, potentially because it didn’t use conventional tools. Despite operating outside of mainstream visual arts could you see its impact on mainstream aesthetics at the time? Was it ever accepted as anything other than iconoclastic by institutions or critics?

⏤ W : We were using lifestyle, popular culture and the media as our tools. Nightclubs were our institutions. We were never going to sit around and wait for someone to give us permission. We wanted our spot next to the McDonald’s commercial and loved infiltrating the mainstream.

⏤ Whenever we were denied access, we would create a duplicate forum ourselves. We had our own magazine, Project X and staged our own national conventions, called The Style Summits. We toured the country, going to all the major cities on networking missions. Nightclubs were a great resource at this time, a bit like the old Hollywood studio system.

⏤ The way our scene collapsed was pretty disastrous, amidst a sea of addiction, political scandal and murder. “Club Kid” became a dirty word. That was our moment of being cancelled. The media only addressed the darkness after that. It seemed like our triumphant beauty, creativity and accomplishments were destined to be lost in the shadows of time. That was the motivation for doing my book, NEW YORK CLUB KIDS. I knew it was time to connect all the dots and clearly articulate how the Club Kid movement came to influence contemporary culture.

IF : What do you think about the ‘gender-revolution’ we’re currently living through?

⏤ W : The great gift that the gender revolution has offered us is the idea of spectrum thinking and intersectionality. It has invited us to see each and every person as a unique identity of their own making, and to communicate with each other as such. I believe that is the most natural and honest posture available to us. We are all born as individuals, and society is slowly coming around to the notion that we should not be conditioned away from that beautiful and vibrant uniqueness.

IF : We exist in a time marked by an overwhelming homogenised idea of what is beautiful. It seems a time of great contradiction; we’re experimenting with surgeries and fillers, make-up and filters in a fight to all ‘look different’ and somehow the end result more often than not feels mass-produced, bland... vaguely familiar. Are we all just conforming again?

⏤ W : Restraint is the hallmark of the visionary. Art is not what you do, but what you don’t do. This subtlety separates the artist from the pedestrian; an awareness of context. It’s important to know when to destroy the things that you’ve created. What is impactful in one moment, quickly becomes oppressive and deteriorating in the next.

⏤ My father raised me with a beautiful quote by Matthew Arnold that I used in the opening of my book “Resolve to be thyself; and know that he who finds himself, loses his misery” •

Foreword Nellie Eden

Facing page Waltpaper in Dee Dee Ramones bathroom at the Chelsea Hotel, 1994. Photograph by ZAK

“NEW YORK: CLUB KIDS” by Waltpaper is published by Damiani

Images BEN CULLEN WILLIAMS

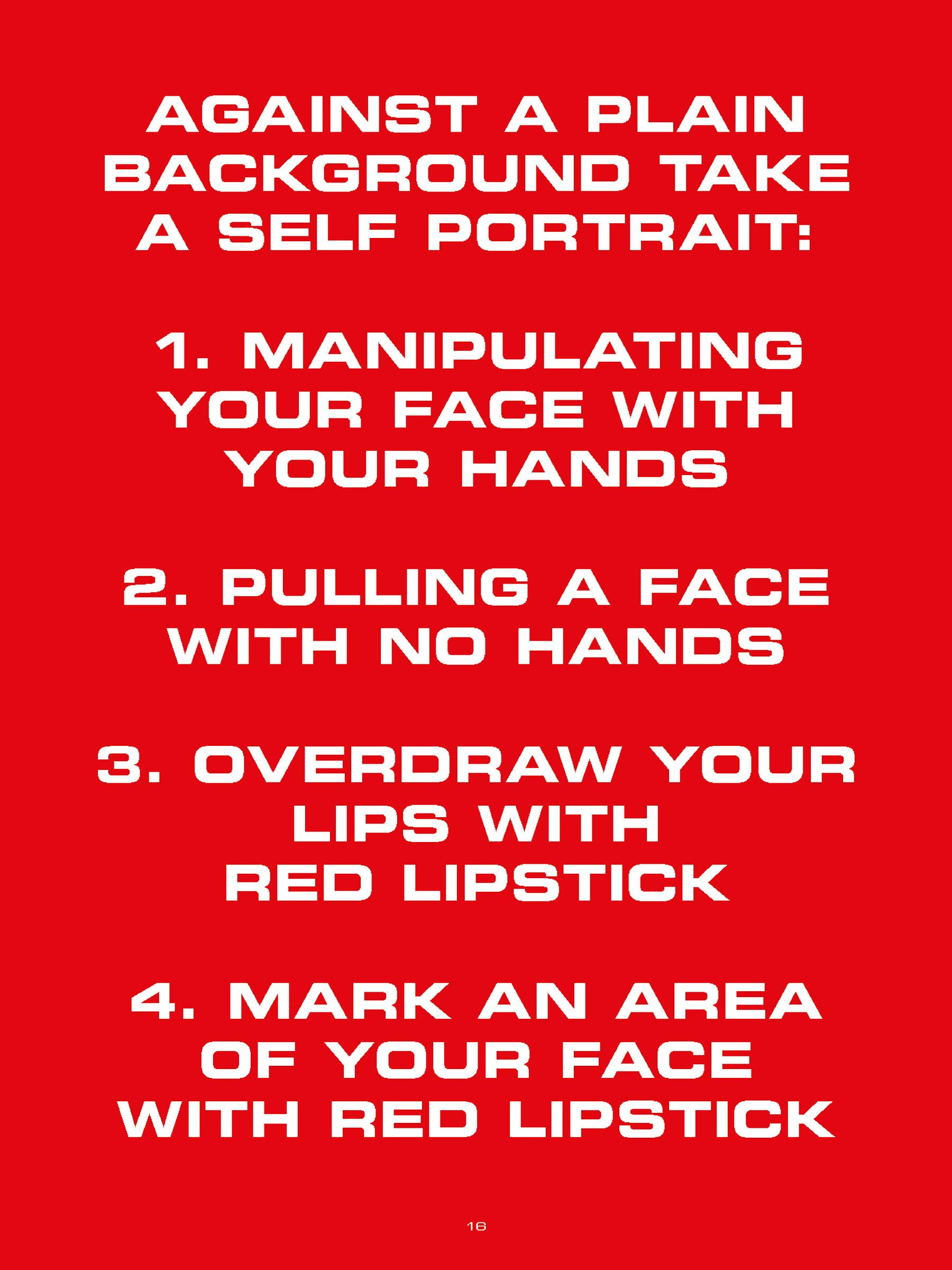

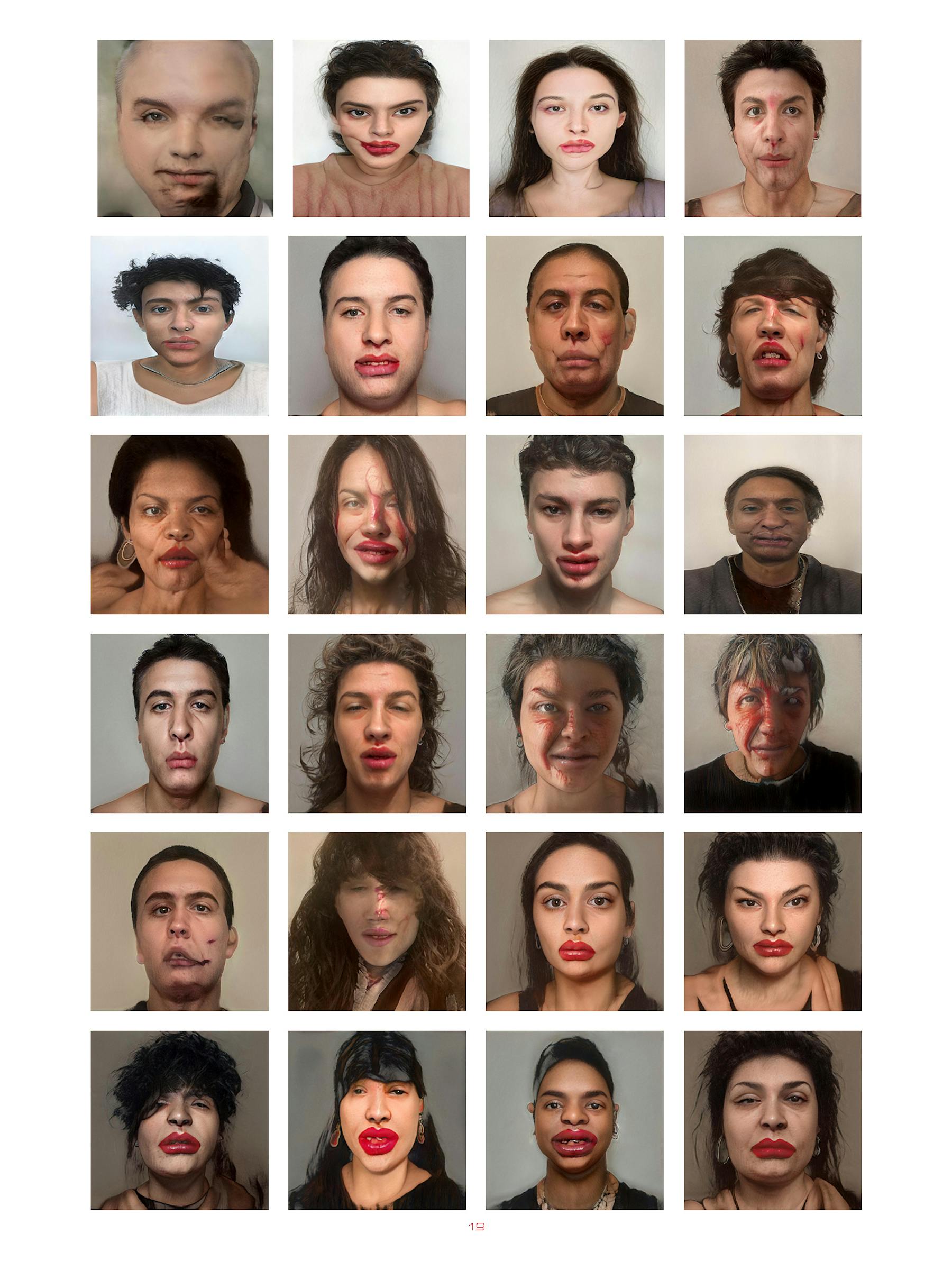

For millennia, artists, mathematicians and philosophers have all tried to define beauty.

Some of the earliest ‘rules’ governing the ideals of human beauty (that we know of) were set by men in authority, who asserted that beauty could be recognised, defined and created according to absolute laws of proportion and mathematics. In classical Greece that meant harmony of form; a perfect body was one on which each feature related in calculably perfect proportion to the whole. If we were to follow these criteria and sculpt a marble person, we should somehow manage to produce something that could be universally recognised (or at least by the Greeks) as beautiful, and far more beautiful than any real human body.

We are captivated, moved and fascinated by beauty.

But why?

In a civilisation whose value system was built so centrally on strength, agility and physical prowess, as embodied in their mythic and Olympic traditions, it makes sense that the ancient Greeks were obsessive about bodily perfection, and that their art reflected this obsession.

Interestingly, this notional mathematical harmony, or rather, a system of principles or rules, that regulated the ideals of beauty appealed to cultural mindsets for over 1,000 years.

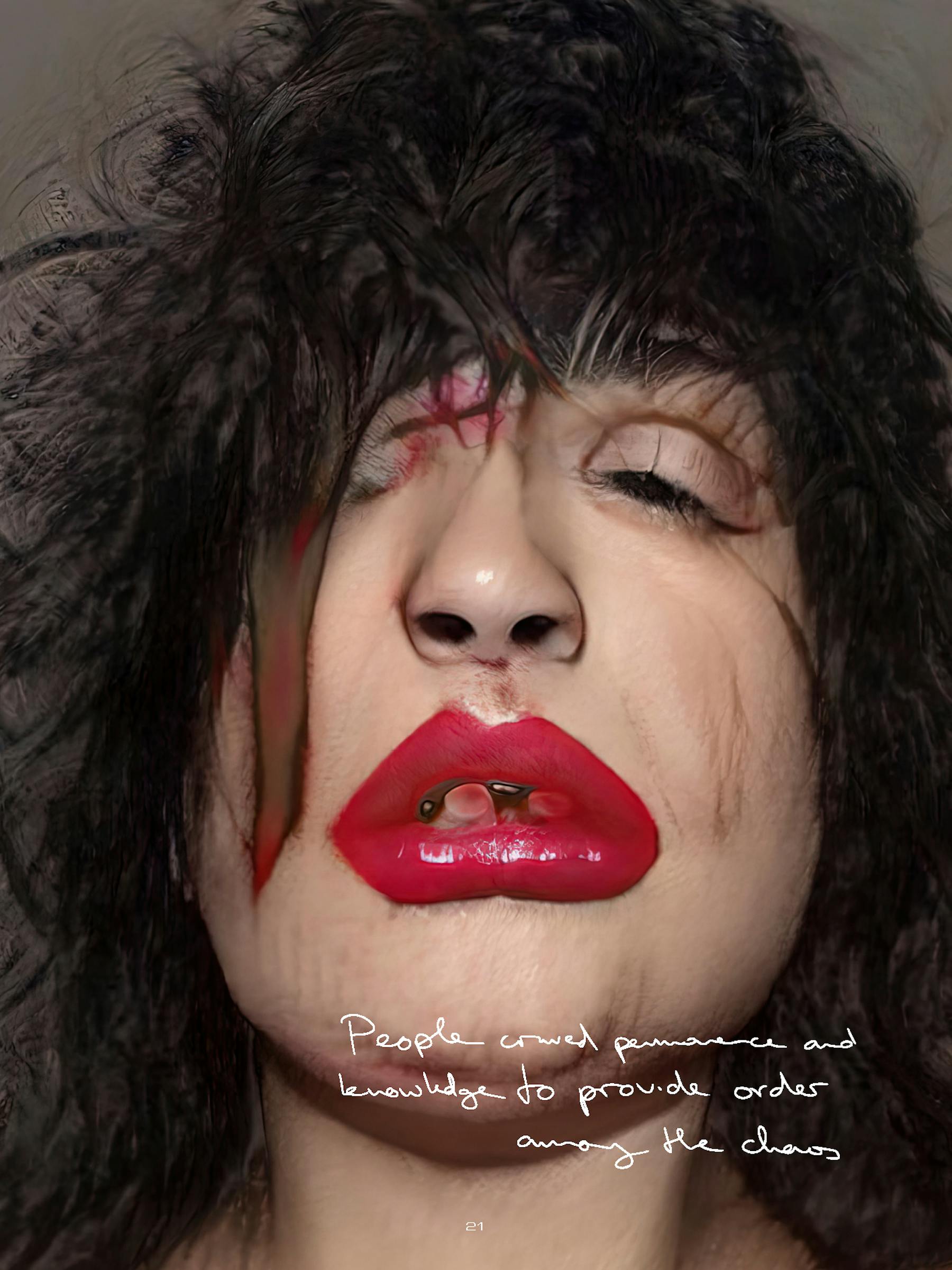

The Middle Ages was an epoch marked by great crisis, when people wanted security in what was around them. People craved permanence and knowledge to provide order among the chaos. The size and strength of Romanesque and Gothic architecture was another expression of this need.

Fast forward to the 15th century, a time of great political, cultural and economic revision. The artists of northern Europe moulded the recently rediscovered art, literature and philosophy of antiquity to the needs of contemporary culture and commerce to cultivate a rebirth in artistic standards. Newly refined ideas of proportion and perspective were paramount in the accurate representation of objects and places, but when it came to human form these calculations were secondary to idealogical expression of character and emotion. Better a face be serene or sagacious than perfectly proportioned. Not that they had to choose; the achievements of the high Renaissance were considered so flawless and unsurpassably true to life that the generation of artists that followed didn’t even try to exceed them in verisimilitude. The Mannerists opted instead for the oddly elongated forms and unnatural poses that nonetheless seem beautiful to us but would scandalise classical Greece.

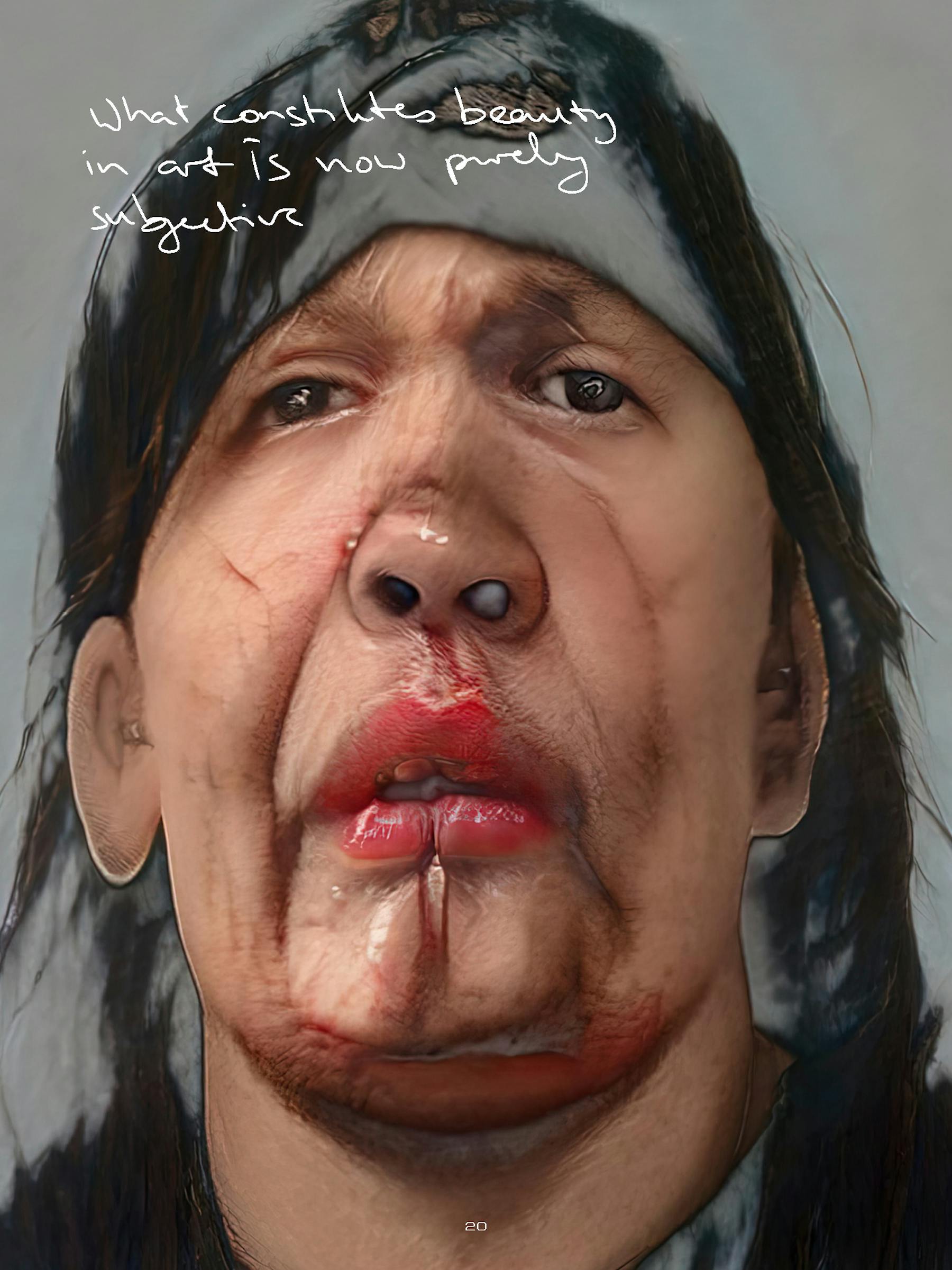

Here we are in the 21st century and formerly objective ideals of ‘beauty’ have been obliterated. What constitutes beauty in art is now purely subjective and often bears no relation or resemblance to earlier historical views.

The past decade and the increasing prevalence of social media have begun a democratisation of beauty standard setting. Every one of us can express and export our tastes worldwide and many of us do. This has created a polytheism of beauty - where not one body type or ethnicity is deified. Instead, trends and fashions that relate to popular film, music, celebrity culture and, of course, cosmetics contribute to constantly shifting definitions.

But by the same means it has created this diversity, social media has also birthed its own unique issues: pressure to conform to unrealistic and often unreal images of perfection and the very real anxieties this pressure creates. Not only that, but we also seem to be stuck between the images we are inundated with on social media and our own preconceived ideals of beauty, which have been shaped by culture, tradition and exposure. All these dissonant voices make sure that beauty contributes its share to the general confusion that characterises modern experience.

So now, in the digital age, when we trust technology to oversee our finances and find our soulmate; when we have algorithms working discretely to display images or information that it knows we will relate to - can we trust these things also to answer the question: what is beautiful? And as we once relied on a system of rules to define beauty, can we now do so again, but in a far more advanced way?

Imagery produced by machine learning is becoming ubiquitous, as is the case with many new creative technologies. Oil paint revolutionised the way works of art could be created outdoors and at ease, away from the studio. Photography, once for a select few, created with cumbersome equipment, is now a part of our daily activities. If history is anything to go by we are just at the start. But, as with photography and oil painting we are beyond the point of showcasing the technology as an end in itself.

We can now use machine learning and AI to interrogate and ask questions about our current human condition, and indeed our evolving relationships with the same technologies that we are harnessing.

Images BEN CULLEN WILLIAMS

Images BEN CULLEN WILLIAMS

Images BEN CULLEN WILLIAMS

Images BEN CULLEN WILLIAMS

In 2016 I visited the War Remnants Museum in Vietnam’s capital, Ho Chi Minh City. I remember the photographs most vividly; these images, mostly from war reportage, had an eerie, grainy film quality that only added to the sense of grim reality that the images evoked. I was shocked and sickened by the blatant and harrowing injustice of the Agent Orange programme that had left generations of Vietnamese dead, deformed and dehumanised. Having fulfilled its primary herbicidal purpose when it rained down on the jungles of Vietnam, the invisible agent seeped silently deeper into the country’s soil, its water, its food. Its victims stand stark and tacit in the photos, rarely making eye contact, lost in their own suffering.

When I first saw these AI images, I immediately thought of Agent Orange.

AI, deep fakes, and their potential for disseminating misinformation have the potential to be as insidious and important a weapon in future conflicts as Agent Orange was in Vietnam. And like Agent Orange its true impact may not be immediately apparent. Algorithms on social media which serve content they know will be received favourably are already fuelling radicalization. We are used to “seeing things with our own eyes,” but now that we can create unreal faces that pass as human with deepfake technology we can’t even trust the most reliable sensory tool any of us have.

Cognitive scientist and author Gary Marcus has said that, “once computers can effectively reprogram themselves, and successively improve themselves, leading to a so-called ‘technological singularity’ or ‘intelligence explosion,’ the risks of machines outwitting humans in battles for resources and self-preservation cannot simply be dismissed.”

AI is responsible for autonomous weaponry. Some claim that it is a good thing as it removes soldiers from the battlefield; others have pointed out that outsourcing our killing to machines removes accountability and conscience from the military equation, and that the technology is vulnerable to misuse or manipulation. From a 2015 open letter by AI and robotic researchers: “It will only be a matter of time until they appear on the black market and in the hands of terrorists, dictators wishing to better control their populace, warlords wishing to perpetrate ethnic cleansing, etc. Autonomous weapons are ideal for tasks such as assassinations, destabilising nations, subduing populations and selectively killing a particular ethnic group.”

This project confronted me with questions I wasn’t prepared for. Fundamentally these images communicate the potential dangers that exist around emergent technology and its interactions with humanity.

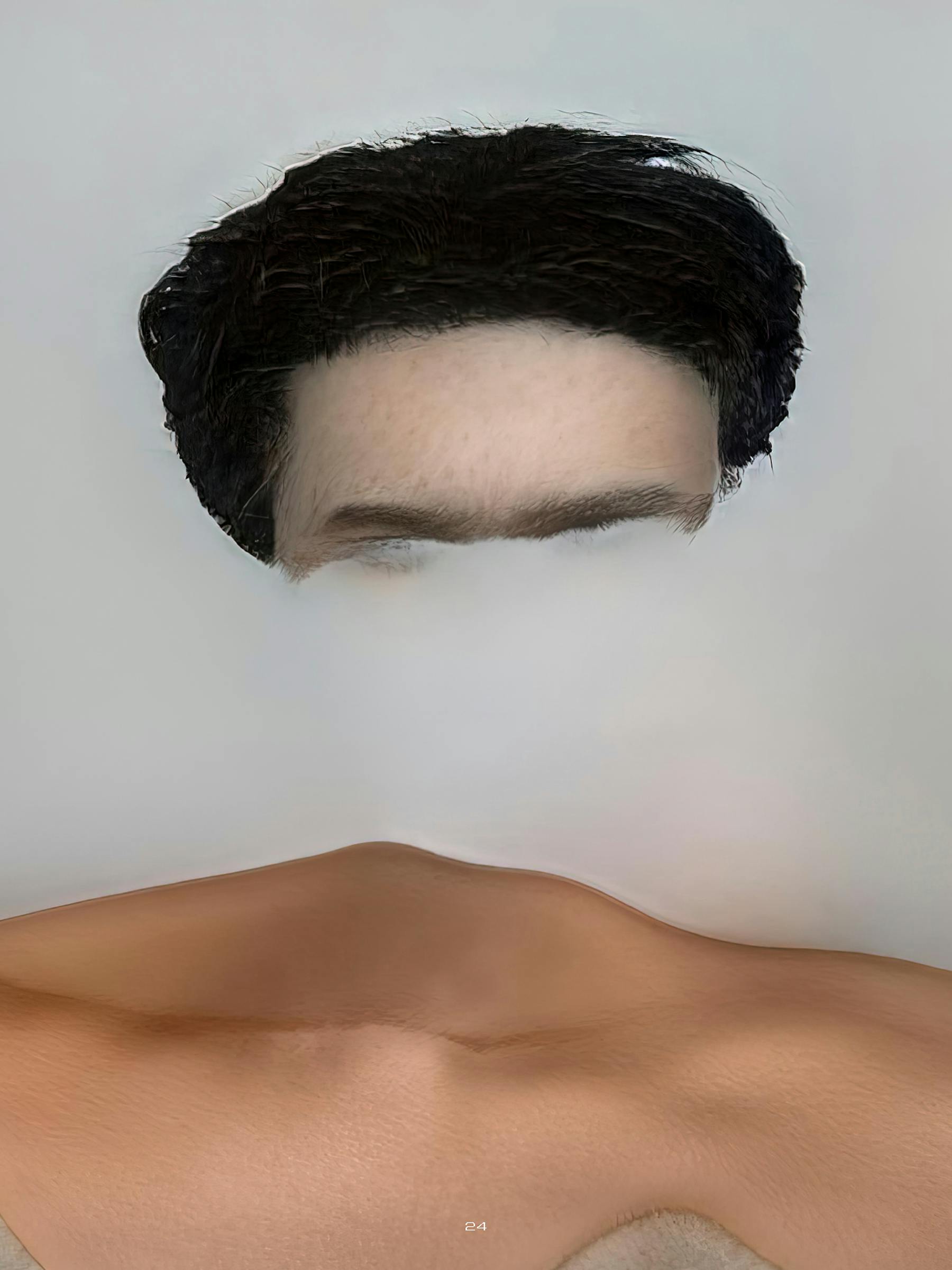

Within this set of images it was the AI process itself that independently interpreted and caused the lacerations and bloody lips on some faces. The images aren’t designed to glamourize violence, in fact they haven’t been “designed” in any sense by any human hand. But the AI’s corruption of the human face may serve as a reminder of the gap between machine-learned perception and ours, and technology’s faithlessness to what we expect of it.

Images BEN CULLEN WILLIAMS