From The Craft Issue

From Lagos to São Paulo, we meet three standout talents from the 2025 edition of the LOEWE FOUNDATION Craft Prize. Their thought-provoking works challenge society and blur the boundaries between art and craft.

Since its beginnings as a leather workshop founded in mid-19th-century Madrid by Prussian artisan Enrique Loewe, the Spanish house has placed craftsmanship at the core of its philosophy. In a continuation of that founding ethos, former creative director Jonathan Anderson launched the LOEWE FOUNDATION Craft Prize in 2016, a platform designed to foster dialogue and exchange with artisans from around the world. The aim: to celebrate excellence and innovation in the contemporary scene, as well as the stories and commitments behind each creation.

This year, the prize was awarded to Japanese artist Kunimasa Aoki by filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar. We sat down with three of the 2025 finalists — Nigerian designer Nifemi Marcus-Bello, Brazilian textile artist Jessica Costa, and American furniture maker Aspen Golann — to reflect on their process and the enduring power of craft.

For Nifemi Marcus-Bello, founder of Lagos-based studio nmbello, form is never isolated from context — it emerges through community, collaboration, and culture.

“Being born and raised in Lagos has profoundly shaped the conversations I explore through my practice,” he says. “My work is rooted in community and collaboration, using design and craft as tools to spark dialogue and build an archive. I’m always looking for ways to engage with the city. Lagos isn’t just a backdrop; it's an active participant in my process.” This immersive and dialogic approach defines Nifemi Marcus-Bello’s creative method. Projects often begin with a question — a point of friction or curiosity — which he then tests against the rhythms and realities of Lagos. “It typically begins with a desire to open up a conversation. I explore that idea within the city, allowing Lagos to inform and challenge it.”

In Lagos, craft and culture are not distinct disciplines but interwoven, interdependent forces. The city’s creative energy — visceral, urgent, plural — infuses his design work with both meaning and momentum. “Lagos is a city with its own pulse. To truly understand it, you have to experience it. It's not so much about collaboration in the traditional sense, but rather, about artists creating with and for their community.”

This ethos is at the heart of his approach to materiality. For Nifemi Marcus-Bello, craft is not a closed tradition but a living, adaptive language, capable of responding to global dynamics while remaining deeply local. That’s why platforms like the LOEWE Craft Prize are, in his view, essential: “They open up a dialogue between commerce and creation, moving beyond ‘craft for craft’s sake’ toward something that can sustain both the artist and their community.”

With his sculptural piece presented at the Prize — part of his ongoing Tales by Moonlight series — Nifemi Marcus-Bello pushes the boundaries between sculpture and utility, proposing a new typology of objects for contemporary living: ones that tell stories of migration, transformation, and material resilience.

TM Bench with Bowl, 2023

510 x 1120 x 400 mm

Recycled aluminium

Based in São Paulo, Jessica Costa is part of a new generation of women textile artists reclaiming craft as both a conceptual and political practice.

In a world increasingly dominated by automation, Jessica Costa’s monumental tufted sculptures — deeply physical, visceral, and handmade — reassert the power of gesture and imperfection. At the heart of her work lies a strong belief in the value of ancestral know-how and collective memory. “I have a long professional journey working with manual textile techniques,” she explains. “And in tufting, I found an interesting path for expansion. It challenges gendered perceptions and traditional views of the medium by approaching textile materiality in a sculptural and three-dimensional way.”

Her practice reflects a broader feminist reclamation within the art world: a growing movement of women artists who transform so-called ‘domestic’ skills into critical and conceptual tools. “Textiles have long been undervalued in art history, often relegated to feminine or domestic spaces. By working on a monumental and sculptural scale, I seek to reclaim their visibility and strength,” she says. “My practice challenges the hierarchies of the art world and creates space for voices that have traditionally been excluded from institutional narratives.”

Deeply influenced by Brazil’s rich textile traditions, the artist draws inspiration from the lacework of master artisans in Pernambuco and Cariri, and from collectives like Artesanato Chave, a São Paulo-based group that reclaims techniques such as crochet as a form of social affirmation and collective identity. “The Brazilian craft scene is incredibly vibrant and diverse. When it comes to textiles, you encounter a wide variety of ancestral techniques that have endured across generations.”

That connection is grounded in her city: São Paulo. A sprawling, fast-paced megalopolis shaped by cultural diversity that plays a paradoxical role in her work. “There’s something contradictory about living in a city like São Paulo while working with hand-made processes. It creates a kind of resistance — and that’s exactly what inspires me about local craftsmanship. Working with my hands humanizes my existence. It restores something the city often takes away.”

Her work resists the sanitization of labor and the erasure of the body. Imperfection, for the textile artist, is not a flaw — it is the source of meaning. “I believe it’s in imperfection that the gesture gains its strength. It humanizes and fosters connection, especially in a world increasingly shaped by AI.”

Sobejos XII, 2024

1300 x 2200 x 500 mm

Wool, resin and wood

Artist and furniture maker Aspen Golann draws on the traditional language of American craft to question the structures of power it embodies and to offer a personal reinterpretation.

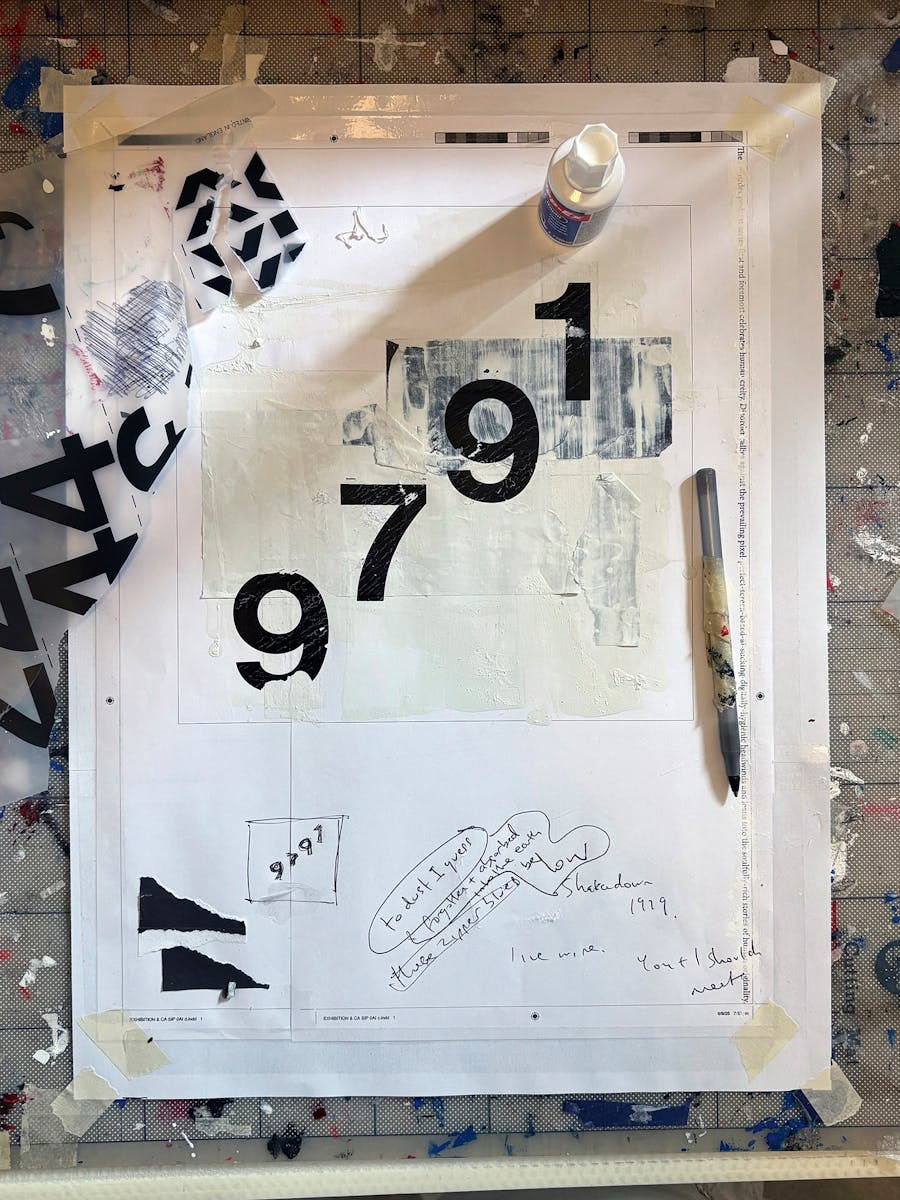

Rooted in traditional American woodworking, Aspen Golann’s practice draws inspiration from 18th- and 19thcentury decorative arts to subvert, from within, the codes of domination, gender, and aesthetics embedded in these traditions. At the LOEWE Craft Prize 2025, she presents Group Work, a sculptural ensemble that reimagines domestic work tools — brooms, brushes, handles — as expressive, almost whimsical objects. “ I came to believe that the best contemporary application of high-style, masculinity-associated furniture skills might be to highlight, elevate, and celebrate objects of domestic labor,” she explains. “These pieces are joyful and strange, but they’re also serious: they’re meant to honor the overlooked labor that sustains everyday life.”

At once critique and homage, her work navigates the contradictions embedded in American craft traditions — particularly those shaped within the halls of early colonial power. As a queer, AFAB (assigned female at birth) artist, Aspen Golann brings a consciously personal and political lens to the refined codes of American design. “I was trained in the aesthetic language of white colonial power,” she says. “But I realized I could use that visual language to explore history and speak honestly. I began to use these iconic markers of American craft — ornate carving, inlaid images, glass enameling — to tell different stories. To speak about social and gender inequity.”

For the artist, the material itself is never neutral. Most of the wood she uses comes from fallen trees gathered within an hour of her home — cut green and shaped by hand using agricultural tools like wedges, sledges, and mauls. “That intimacy with the material contrasts sharply with the traditions I was trained in. Those objects were made to display wealth, power, control. I use that language to say something else.”

This tension between legacy and resistance sits at the core of her work. Through craftsmanship, she reclaims both skill and symbol, bending inherited forms into personal and collective statements. “Hijacking and recontextualizing these symbols is a way of finding an authentic voice, reclaiming power, and expanding the potential of traditional woodworking,” she says.

Her selection for the LOEWE Craft Prize marked a turning point. “It’s one of those rare moments when I begin to believe that my obsessions — the things I make, think, and shape — might resonate beyond me,” she concludes. “That these objects aren’t just personal curiosities, but part of a broader cultural conversation. It makes me want to speak more clearly through my work. To be braver, louder, and more honest in what I make.”

Group Work, 2024

680 x 1600 x 750 mm

Hard maple, brass, broomcorn and waxed linen