From the Faces issue

On June 7, Satoshi Kuwata was awarded the Prix LVMH 2023. His brand, Setchu, is a textile translation of the idea of good taste, borrowing from both Japanese culture and European know-how. Between fertile metaphors and implacable formulas, meet the designer.

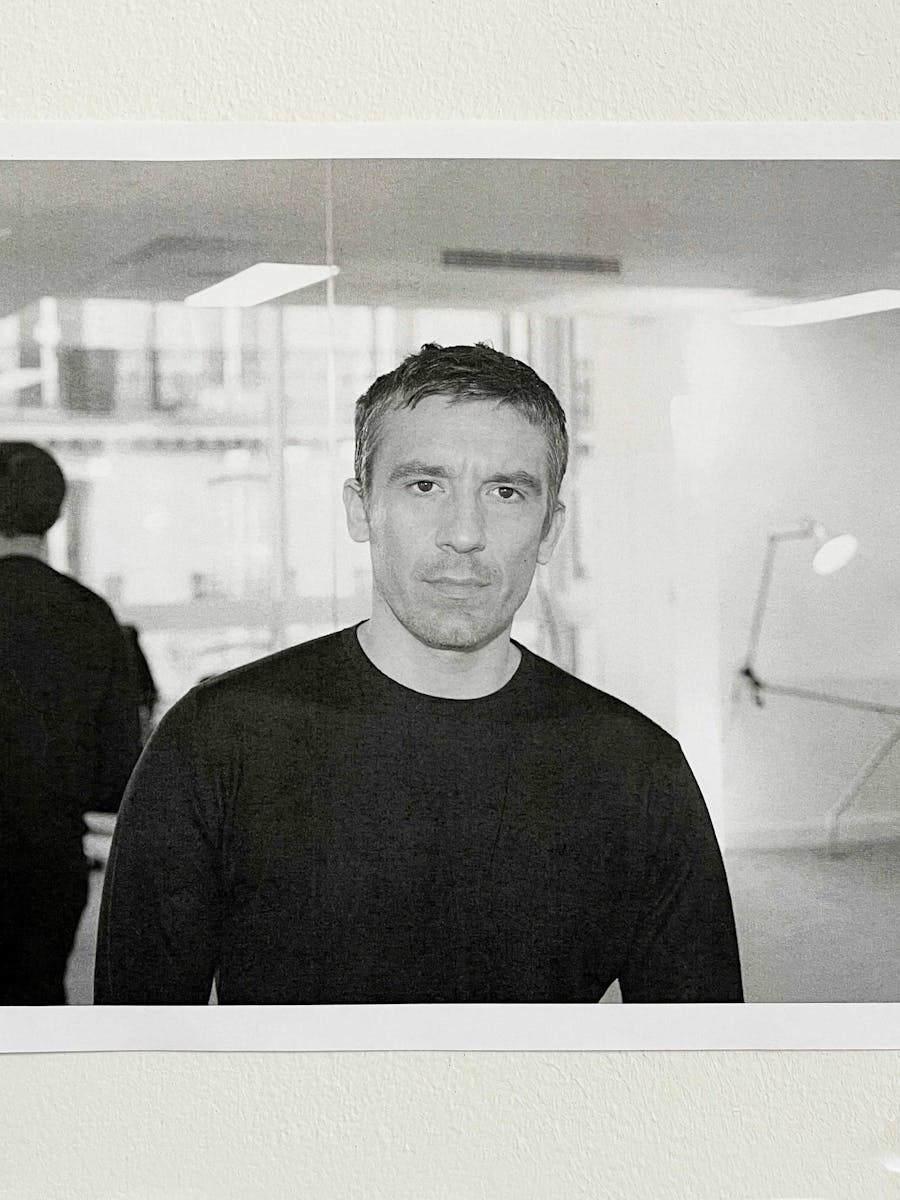

Having only launched his brand in 2020, Satoshi Kuwata is already a fashion veteran, having worked with Riccardo Tisci at the Givenchy studio, Gareth Pugh's more delirious studio and, what he considers a seminal experience, H. Huntsman's workshops on London's famous Savile Row. From his studies at Central Saint Martins to his years as a tailor and then designer, Setchu's founder is on a quest for meaning. For him, every creation must reconnect with its cultural origins in order to better integrate into our daily lives. Setchu's collections blend pragmatism and minimalism through modular pieces and genderless cuts that guarantee adaptability at all times. Raised in the Japanese countryside and now based in Milan, Satoshi Kuwata became famous after winning the LVMH Prize, but wishes to remain anonymous, preferring to master his craft rather than his communication tools. He is truly Setchu, the Japanese term he gave to his brand to describe positive compromise.

This year, you won the LVMH Prize. Was the competition fierce?

Of course I did! My friends told me I'd won because I was the best. But, more objectively, everyone was the best or we wouldn't have been here. I know most of the candidates and I know we all work very hard. But the atmosphere wasn't competitive. We exchanged a lot with each other and supported each other. One thing I'm particularly proud of is that the jury unanimously chose me as the winner. That doesn't happen very often! Most of the time, each member pushes one candidate over the other. This time, they all agreed.

What are your brand plans following the award?

This sum [400,000 euros] enables me to pay the suppliers, factories and workshops I work with, as well as to develop future collections. The company is growing so fast! So I have to buy more fabric, produce more and, in turn, spend more, but I don't spend anything unnecessary.

You're an avid fisherman and even claim that your designs are wearable for fishing. Does this activity, which requires a great deal of patience, help you approach your career in fashion?

I love fishing because it reminds me of where I grew up, in nature. What interests me about this activity is what it teaches us about the natural elements. From one second to the next, the water can change completely. In a way, fishing makes me sensitive to changes, teaches me to stay alert to sudden movements. It's a bit like sensing the zeitgeist in fashion. My brand isn't concerned with trends, I'm more interested in producing a timeless wardrobe, but to do that, you have to be able to identify trends and remain reactive.

"Setchu", the name of your brand, derives from a Japanese expression - "Wayo Setchu" - denoting a compromise between Japanese and Western cultures. I have the impression that you are the first to put into words a phenomenon that, in fashion at least, has existed since the 90s.

Your comment is absolutely true. For example, Margiela's Tabi is setchu. A perfume, made up of a top note, masculine and feminine notes, is setchu. This concept has become the name of my brand. Let me explain. "Wa" means "Japan". In fact, some Asian countries use the term "Wa" to refer to Japan. And "yo" means "outside Japan". Basically, it characterizes the whole of Japanese culture in Japan and outside the country around the world. Finally, "Setchu" means "put together, gathered" in the manner of a compromise. For two hundred years, Japan was hermetically sealed off from other countries by imperial decisions designed to protect Buddhism and Shintoism from Christian influence. So, when the country opened up to the world, many objects from other cultures entered Japanese culture at such a speed that the Japanese didn't have time to digest them and make them their own. They just integrated them into their own. The aim then became to find a form of beauty by bridging a cultural gap. "Wayo setchu" is this compromise between Japanese and Western cultures. Many people have told me that there is no English equivalent to "setchu". Personally, I'd love to see the term "setchu" become as common to Westerners as "sashimi, sushi, tempura, tofu."

By offering timeless, gender-neutral collections - the modern criteria for fashion brands - do you place yourself in the category of innovation or invention?

I think I have to be both. What my customers want is something I've produced, something I've created. Take the inventor of Dom Pérignon. He invented this now world-famous white drink and a bigger bottle that wouldn't break. I want to be that kind of person. The story of Dom Pérignon is both that of an invention and that of the creation of a useful object. My brand was born of this desire to bring together clothes that last and a fashion story that holds up. You always have to give meaning.

The theme of this issue of Exhibition is "Faces". What do you think of contemporary thinking around individuality and the importance of developing unique personalities in our digital societies?

Since the pandemic, people have been spending a lot more time on Instagram, which has become one of the only ways to stay connected to the outside world. The pandemic has woken us up, and people want to reconnect with things that are truer, that retain meaning over time, and clothes are indicative of this way of apprehending the world. I believe that the quest for identity associated with more timeless clothing will continue to develop strong personalities by revealing one's philosophy of thought. Because "timeless" doesn't mean boring! On the contrary, this phenomenon reinforces the importance of branding at a time when the role of the designer has changed. If he remains one of the brand's emblematic personalities, it's simply because he takes on so many responsibilities. At Setchu, this is my case for the time being, but I'd like to see responsibilities shared over time between creation, speaking engagements, etc.

Your face was little known to the general public before your exhibition thanks to the LVMH Prize. You seem discreet, going against the grain of the age of social networks and star art directors.

Yes, I think timelessness is a positive creative position. A garment should be able to be worn in different ways. You can borrow it from your partner and put it to another use, turning a cardigan into a dress. So, instead of buying three cardigans a year, you buy just one, but wear it in three different ways. That's how you never get bored with your clothes! At Setchu, you can buy just one piece per season and look different every day by changing the buttoning or pairing it with another modular Setchu garment. It's to find this adaptability that designers need to be technical, and why I'm so keen on this mastery as a designer.

In fact, your definition of eco-fashion includes modular pieces that can be worn in different ways.

Yes. In my opinion, timelessness is a positive creative position. A garment has to be wearable in different ways. You can borrow it from your partner and put it to another use, turning a cardigan into a dress, for example. So, instead of buying three cardigans a year, you buy just one, but wear it in three different ways. That's how you never get bored with your clothes! At Setchu, you can buy just one piece per season and look different every day by changing the buttoning or pairing it with another modular Setchu garment. It's to find this adaptability that designers need to be technical, and why I'm so keen on this mastery as a designer.

Thanks to this adaptability, your garments also invite creativity, with styling integrated right from the manufacturing stage. Is it to extend the creative dialogue with your customers?

When I think of my customers, I don't think of them in the same way as a work of art. I certainly want to live in an artistic and creative environment, but we must never forget that what people want is clothes for their everyday lives. They want a white T-shirt. At Savile Row, my boss used to say to me, "Satoshi, tailoring is not draping. Tailoring is about sculpting the body." I totally embrace this sculptural approach. If you look at my collections, there are a lot of references to ceramics from the 1960s and 70s, because I love that. Kanjiro Kawai is my favorite ceramist and a friend of my grandfather. Every piece he creates is so beautiful and modern that it looks like it was made the day before! I try to recapture this feeling in my creations. Each cut is pragmatic but at the same time slightly twisted so as to be timeless and suitable for everyone. You can dress a lot of people with just one garment. I want to be able to dress even my father!

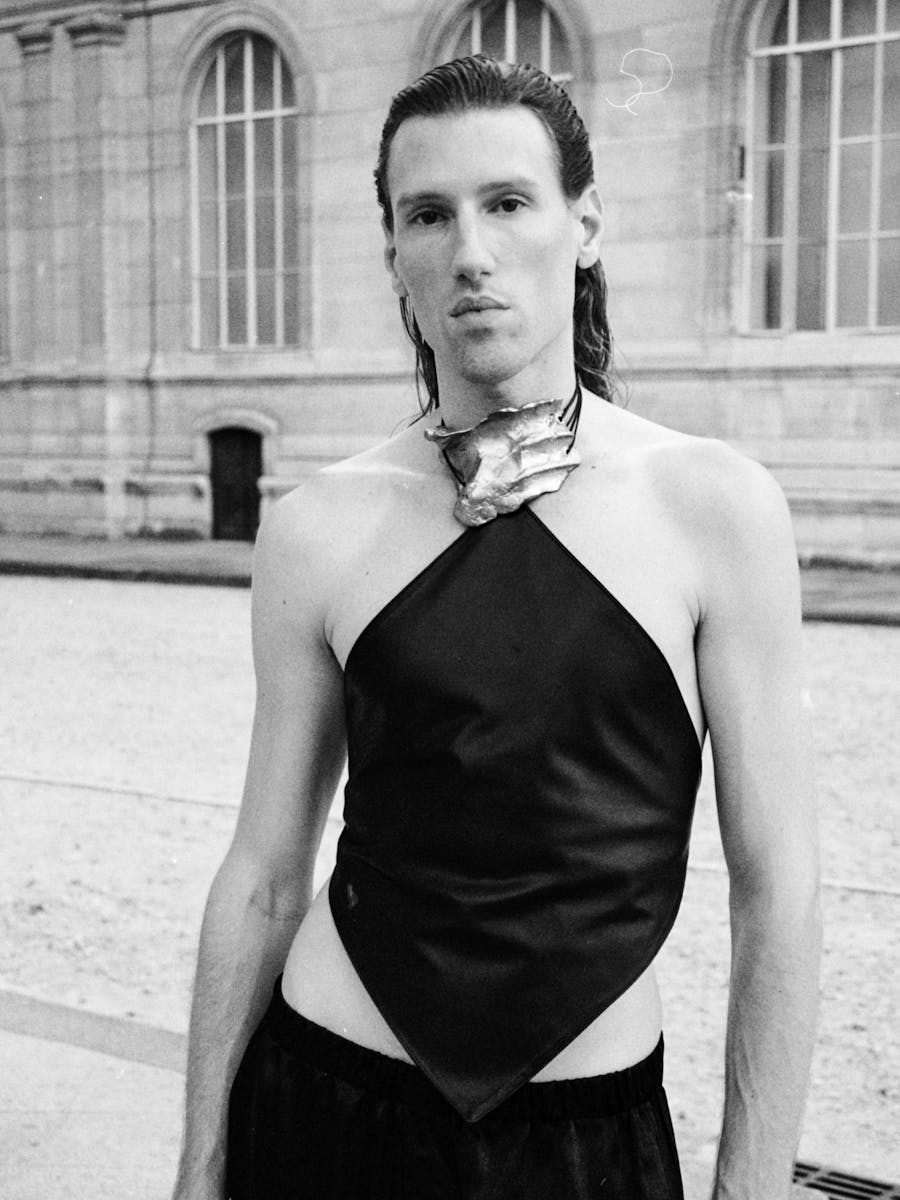

Japanese fashion tends to cover the body, while Western fashion looks for ways to reveal it. Where do you fit in? Setchu?

Savile Row taught me just how gendered Western fashion can be. It's a very masculine industry that misunderstands the female body, not out of discrimination but out of ignorance. So they create suits with emphasis, like corsets. Japanese fashion, on the other hand, tends to throw away the fabric and drape the body all around. For my collections, I use Italian fabrics because they're the best. And I've noticed that the closer you create clothes to the body, the less the fabric lasts over time, because strong physical pressures induced by movement are exerted on the fabric. So I do "relax fit", neither too close to the body, nor too oversized.

You're looking for ease of dress, and place a lot of emphasis on the back, which is often overlooked in designs. Why is this?

When you wear my clothes, you become a model. I don't want pockets on my jackets. They're a nonsense because they're too heavy and inevitably alter the silhouette. I want to keep my cuts straight and uncluttered. As for the back, it's the part of the garment where you can really show respect to others. Nothing is more polished than a well-made back. When you say goodbye to someone and then turn your back on them as you leave, being well-dressed until you turn on your heels is a sign of respect. You'll leave a good impression.

In the Spring-Summer 2024 collection, there were ironing marks on the garments - an image-maker's obsession! - which were deliberately applied because, as stated in the note of intent, "nothing is left to chance". Is this refusal to consider chance as an eventuality a metaphor for your relationship with creation?

Yes. Nothing happens by chance. Things happen for a reason. We live in a capitalist world with all this mass culture that has shaped me. As a child, when I saw a can of Coca-Cola with defects on the store shelves, I thought it was better than the others. Even artistic accidents don't happen by chance. On the other hand, not every creation has to be useful - at least for the time being. In our industry, everyone works hard and a lot of negativity circulates. But you have to be indulgent with yourself and your ideas, even when you don't think they're great - they could have been worse! You have to let creativity emerge.